Wow! It's been a long time since I've been over to CC Mixter!

They've been as busy as ever over there, creating a bunch of great new remixes using my Hepepe and Me acapella track.

MC Jackinthebox, one of my favorites, created a CC Chickster track using samples from many of the CC Mixter female vocal staples.

Then I find out that Hepepe created a new song using the acapella track that I originally added to his song (Hepepe and me), Byrd of Cool. He created a completely different track and called it:

Lisa and Me.

How cool is that?!

I've been fishing around in CC Mixter because I'm in the process of editing together a ton of Second Life videos, and I needed music for them.

As usual, ten minutes over at CC Mixter and I'm all set for soundtracks!

Oh yeah, this Dr. GoldKlang remix rocks too... (And it mixes me with death metal vocals, which I totally dig :-)

http://video.lisarein.com/sfsu/..I wanted to get this up quick so it would be easy to tell people at the ACM conference.

Looks like I never told you that I HTML'd my Copyright/Creative Commons Paper and Guide.

It's all indexed and such so it should be easier to get around in.

Don't forget the handy pro/con table for Creative Commons Licenses

thanks!

lisa

Due to an unexpected hosting emergency, my Songs From The Commons podcasts were down for a week or so.

They're back up now on the Mondoglobo site, and hopefully the blog part of it will be back soon too.

I've created my own archive that will always be available here as a backup too.

I have show 16 in the works. All this other stuff has kinda taken over lately, but I'll try to wrap it up this weekend.

This show features great stuff from indieish.com as well as some great stuff from CC Mixter's Copyright Criminals contest. (Note that I had previously linked to indyish.com by mistake - but it turns out they're another great resource for Indy artists, so you should still check them out.)

All the info, with direct links to all media, is available on the website:

Songs From the Commons - Show 15

The next show will be July 17th! Thanks for being so patient guys!

I think my equipment's ok now, so I'll be cutting together my next podcast over the weekend.

Send me your favorite tracks and I promise I'll play them on the show.

Just email me at lisa@lisarein.com.

Thanks!

These will start to be more regular now. Sorry for the hold up!

I've created a student licensing guide for using content in mixed media production and licensing your own production when you're done.

The final guide is available

Here. (.doc) file

A longer winded version of the same information contained in the Guide (with historical references)

is available here:

Word File

Text version.

My pros and cons table comparing Creative Commons 6 main licenses (and the Public Domain) is here:

Pros and Cons of Creative Commons Licenses

(As an idealist and a skeptic.)

Here is the full text of the long winded report:

A Review of the Current State of Copyright Law

By Lisa Rein, lisa@lisrein.com

April 12, 2006

Traditional Copyright

To understand the current state of Copyright Law, it is helpful to first understand the Founding Fathers original intentions and the guidelines that were originally set forth in the Constitution. Article 1, Section 8 states that Congress has the power "To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries." (U.S. Constitution 1788) The Copyright Act of 1790 specifies the Copyright term at 14 years, with the option to renew once for another 14 years, for a total of 28 years of protection. (Copyright 1790) After that, the work goes into the public domain, so others can use it and benefit from it. (After a work goes into the public domain, publishers are free to print it up and sell it without compensating the original creator.)

The Constitution is quite clear about who Copyright was ultimately supposed to benefit: the public. The very first Copyright act, the Copyright Act of 1790, described itself in its very first sentence as "An act for the encouragement of learning..." The government recognized that creators needed compensation in order to create, however the ultimate goal of creating new, better works was to benefit the public, not only provide private gain. The whole purpose of Copyright was for creators to have the exclusive right to make certain uses of their work for a limited time however, after that limited time, all uses could be enjoyed and reused freely by any member of the public. Traditional Copyright intended that neither the creator nor the public should be able to appropriate all of the benefits of a work. Creators need to gain some benefit or they wouldn’t create. The Public needs creations to build upon and enjoy. The promotion of learning and the arts is another key consideration that the Founding Fathers had in mind when they devised this system.

The economic perspective behind Copyright is something called "The Copyright Bargain. (Litman 2001) This "bargain" is the deal entered into between Copyright holders and the general public. The Copyright system is designed to give some market-based financial compensation to the people who created works and the people who distributed them (publishers). However, the other side of this “bargain” is that the long-term rights for the use and reuse of those works be reserved for the public and other authors of the future. (Rein 2003)

The Copyright Term

One of the most controversial Copyright issues today has been determining the length of this Copyright Term. The Constitution specifies that Congress is "securing for limited times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries." (U.S. Constitution 1788) For years, corporate Copyright owners, such as the Disney Corporation, have been successfully lobbying Congress to continuously extend the term on the basis that Congress has the power to determine what "limited" is. As a result, the Copyright term has been extended 11 times in the last 40 years. The current term is 70 years after the death of the creator, and 95 years after first public distribution of "works for hire," or 120 years after the creation date, whichever comes first. (Copyright 2003) A "work for hire" refers to a work where the creator signs off on their rights as part of the deal. Theoretically, the artist does this in exchange for a greater sum of money, since he won't see any further financial benefits from the work after the initial payment. From a company's stand point, “works for hire” are easier to deal with because the corporation would otherwise have to clear usage with the artist every time it wanted to reuse the media in some way. Whether this is good or bad depends on which side of the deal you're on. If you are an artist, you always want to retain or share the Copyright, so you can stay in the licensing (and compensation) loop if the work is reused later. If you are a producer or part of a production company, however, you won't want to worry about having to find the artist later to get their permission for every little reuse. So a producer wants the artist to agree to create work as a “work for hire” whenever possible. These latest extensions only apply to works created after they take effect. This means that the term varies, depending on when a work was created. This adds another layer of complexity to the already confusing prospect of correctly determining whether a historical work has fallen into the Public Domain.

The Copyright Term has now been extended to be longer than most humans' life span, so creators rarely live long enough to see their works go into the public domain. Copyright holders are able to profit from their works throughout their lifetime and often their offspring or whomever inherited their estate after their death also profits.

Too Complicated for the Public To Understand

What started out as a simple document that fit on half a newspaper page has bloated into a document of over 290 pages. As a result, students and teachers aren't really sure what the law is, and often err on the side of conservatism. This has led to what is called a "chilling effect," where art, education and research are not allowed to blossom to their full potential for fear of legal repercussions. With artists and creators unsure of their legal standing, many choose to create other works that might be "safer" considering the unknowns surrounding the use of Copyrighted works. The scientific community has also felt the repercussions of this chilling effect, because they are afraid to borrow from the research of others to advance new scientific solutions.

Copyright Infringement and the DMCA

"Infringement" is violating a Copyright-owner's exclusive rights. The law does not require that the infringer be aware they are doing so. Harm does not need to be proven. (Litman 2001) As an artist deciding whether or not to include pieces from the works of others, you want to make sure you're not infringing on any one else's rights, so you don't get sued.

What happens when you put something up on the Internet without permission and the Copyright holder finds out? The Copyright holder can accuse you of violating something called the Digital Millennium Copyright Act and send your Internet Service Provider (where your files are hosted) a "takedown notice." (DMCA 1998) By law, according to the DMCA, your ISP has seven days to respond. Theoretically, a week is plenty of time to contact you, find out what's going on and, if you are infringing, ask you to take it down. In reality however, a week is not very much time. What if the “takedown” letter is sent on a Friday and not read until Monday? Whether that's one day or three days is unclear. The Copyright holder can demand that it be taken down pending investigation and, often, this is done before you have an opportunity to defend yourself. According to the DMCA, a Copyright holder need only have a "good faith belief" that his rights are being infringed to issue and "cease and desist" letter (a "c and d" or "takedown notice").

The reality is that ISPs rarely take the time to investigate or send a letter back saying that they have checked with the violator in question, who claims they own the material and is disputing their claim. The larger ISPs have lawyers and know their rights, but the smaller ISPs don't always know their options and don't want to pay a lawyer to find out what they are. So the easiest thing for them to do, often, is take the site down pending further investigation. The Digital Millennium Copyright Act is not very straightforward and is difficult to understand. Its provisions are still being debated, but it's the current law in effect. Even after you take the material down, you can still be charged anywhere from $5000 to $50,000 per violation. Defending yourself costs money, so having any sort of conflict becomes immediately expensive.

Fair Use

“Fair use” is a defense, used after the acknowledgement of infringement (unauthorized use) has actually taken place. The Copyright Act of 1976 specified in writing a collection of provisions for Fair Uses that, up to that point, had only been understood via "Common Law" precedents set by judges ruling on a case-by-case basis over the years. (Schultz 2006) Section 107, Title 17 of the Copyright Act of 1976 explains "Fair Use" in a fairly straightforward manner defining a number of specific acts that don't count as Copyright infringement. (Copyright 1976) These “acts” include reproducing "part or all of a work for the purposes of: criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship or research." (Copyright 1976) Parts of the definition are purposely left up to interpretation. For instance, what exactly constitutes criticism, comments, news reporting, teaching, scholarship or research? This act also sets forth what has come to be known as the Fair Use Four Factors Test, which is used to determine whether a use qualifies as “fair.” In a nutshell, it depends on whether such a use is commercial or non-commercial, the "nature" of the work (whether it is factual or fictional) how much of the work is used and if such use has some effect on the potential market value of that work. Although the text of Section 107, Title 17 of the Copyright Act of 1976 states very clearly that "multiple copies for classroom use" is included as “fair use”, recently adopted policies across academic campuses nationwide have required teachers to cut back on the amount of copied material actually used in class, forcing them to ask themselves if they "really need" excerpts from one book or another to make their point in class. Such is another example of the "chilling effect", this time on the educational process.

Copyright is "Automatic"

The Copyright Act of 1976 also designates that newly created works are Copyrighted "automatically." The Copyright is attributed to the work without having to register it in the Copyright Office, as was previously the case. A work is copyrighted as soon as it is "fixed in a tangible medium." (Copyright 2003) Examples include taking a photograph or writing down a story on paper or recording a song on to a tape. This automatic protection has both benefits to creators and potential pitfalls for creators who may not wish for their works to be "locked up" after their death.

The loss of the Public Domain

Arguably, one of the greatest casualties of a perpetual Copyright Term is the eventual loss of a Public Domain. There are many who would say that the public doesn't lose anything from not having a public domain anymore, and that it's OK for people to pay to use creative works in perpetuity. They might also argue that the Founding Fathers just hadn't thought in terms of our modern concepts of intellectual property when they were first devising the concept of Copyright in the early acts.

Eldred vs. Ashcroft (2003)

The last Copyright extension, the Sonny Bono Copyright term-extension act, added the last 20 years to the term, effectively pushing the pubic domain work's release date so far out that now no creative work is scheduled to go into the public domain for 16 years. Given the current sentiment, Copyright term is probably going to be extended again, and the concept and existence of “public domain” may be lost forever. The "Copyright maxima lists" feel that there's nothing wrong with the loss of a public domain. However, most would agree that this viewpoint ignores the other half of the Copyright Bargain, where the public eventually benefits from the work.

Eric Eldred, a public-domain publisher who had been making HTML'd versions of public domain works available on the Web, cried foul, and launched a case against the government calling the constitutionality of the last 20-year extension into question. At the same time, on a parallel track, Eldred, with the help of many legal academics from universities around the country, set out to attempt to create a voluntary public domain. (Lessig 2002)

It is because of this dwindling Public Domain that Creative Commons was created. Creative Commons is a non-profit entity created to offer alternative licensing to that of traditional Copyright. Creative Commons licenses allow certain uses "up front," without requiring the explicit permission from the Copyright holder, while still preserving all other protections of existing Copyright Law. Creative Commons was started in 2002 in direct response to the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998 (Sonny Bono 1998), when this legislation extended the Copyright term to a length that stopped many works from going into Public Domain. This legislation deprived Public Domain publishers from being able to publish these works. (Eldred)

In Eldred vs. Ashcroft, the Supreme Court ruled that these endless Copyright term extensions were constitutional, based on Congress' right to determine what constituted a "limited time." (Eldred vs. Ashcroft 2003)

Creative Commons Licenses

All Creative Commons licenses require attribution. After that, you have two options: allowing/disallowing commercial usage and allowing/disallowing derivative works. Furthermore, if you do allow your work to be remixed to create another "derivative work," you may optionally require that such works are released under the same license as yours. This way, remixes of your work are also available to remix, rather than being "locked up" under another license.

This "share-alike" provision embodies the true spirit of Creative Commons: creating a voluntary Public Domain in response to the ongoing loss of the "real" Public Domain due to the perpetual length of the copyright term. However, many people don't want to place any restrictions on reuse, fearing that such restrictions may serve as a deterrent to usage. (See my attached "Pros and Cons of CC licenses" table.)

Creative Commons’ licenses work backwards from existing copyright to enable you to make exceptions to the normal copyright rule, and allow the uses you want without losing any of the "automatic" protections of "traditional copyright." Every license allows the work to be copied and distributed in any format, displayed or performed publicly, or webcast (a "digital public performance"). Every license applies world-wide and is irrevocable. If that "irrevocable" part sounds scary, fear not. Another feature of Creative Commons’ licenses is that they are non-exclusive. So putting your work out under a CC license can never interfere with anything else you choose to do with that work in the future.

These licenses take on different perspectives depending on whether you are using work licensed by others for your work, or licensing your work for others. When choosing content, a producer needs to first consider whether it is okay to use the source material as he would like in his own production. His second consideration is to confirm that the license for that source material will also allow for whatever license chosen for his own works’ redistribution.

The most restrictive license, and perhaps the "safest" to use until you understand the different options, is the "Attribution, Non-commercial, No-derivs" license. Like all Creative Commons’ licenses, it requires attribution and a link back to your site if the work is made available for download on a website. This license is sometimes called the "free advertising" license because it enables others to do your duplication and re-distribution for you. People can download it and share it, but they are not allowed to modify it in any way. So, for example, you can use songs licensed under this license as a soundtrack in your film, but you are not allowed to run that song through a filter to make it sound different in any way. You are also not allowed to sell the song when you’re done, without contacting that Copyright holder and obtaining their explicit permission. This license allows only for usage in non-commercial environments (schools, non-profits, students, and, potentially, a person's personal website), and requires that the work be included in its entirety. This doesn't mean that you have to use the whole song, but that any part you do use is “verbatim,” and not altered or remixed to create another "derivative" work.

Now, in the "real world," if a commercial filmmaker, found a Creative Commons’ licensed work under one of these licenses, the chances would be pretty good that you could contact the Copyright holder and pay them some money and get their permission for use. As an enticement to the original artist, the license holder might specify the use was for a full length commercial film and likely to get a lot of exposure. Big Hollywood studios have entire departments of people who are set up to handle this kind of negotiation, but the average "independent" filmmaker does not have these resources. He would have to forfeit this option if an opportunity later arose to make money from his creation. For this reason, independent filmmakers are more likely to choose music that gives permission to sell their new creations up front, so as not to create more complications later.

There are two or more sides to almost every aspect of these licenses. Each of the perceived "restrictions" has the potential to be perceived as having positive or negative consequences. For instance, allowing derivative works represents both a loss of control over how your work may be used, but it also puts you on the receiving end of more "free advertising." This is true because when others use your work, they will be promoting your work along with their own derivative creations by providing attribution and a link back to your own website (as required by all licenses that allow derivative works.) Allowing commercial works lets others profit from works containing your work within them, but it also makes using your work an option to a whole different professional class of people. Requiring that others "share alike" ensures that all derivative works will themselves be made available for others to reuse, but it may be a deal breaker for a professional filmmaker whose other contractual obligations do not allow them any flexibility.

In the same vein, there are definitely two sides to the argument for placing one's works directly in to the Public Domain. On the positive side, you can be sure that your work will live on after you do. People will make copies of your work in different formats for you to preserve the work, and you can list your works among numerous historical works in many of the public domain archives available. Your work will most likely have derivative works created from it because artists will often create from existing work simply because they know they can. But really, these days, placing your work in the Public Domain is more of a political statement, should you wish to make that point that the information your work contains is so important that you release all claims in order to just "get it out there." Or, sometimes, this action represents that your work is built upon works already in the Public Domain, and therefore you do not wish to lock up your derivative work based on that Public Domain work under the restrictions of traditional Copyright. (Disney's Snow White is a good example of a derivative work based on a Public Domain work that is now locked up under Disney's traditional Copyright for its film.) One might also place their work under the Public Domain as an act of support and dedication towards rebuilding our Public Domain.

Since Creative Commons licenses are now available, it's less common for one to give their rights away to make their point. A person can make their work available for uses of their choosing, while still retaining complete control over other uses.

The attached table summarizes the pros and cons for each of the six main Creative Commons licenses (and the Public Domain).

References

Copyright Act of 1976 (1976)

Copyright Act of 1976, Section 107, Title 17 (1976)

Copyright Act of 1790 entry, Wikipedia (n.d.). Retrieved

April 6, 2006, from

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyright_Act_of_1790

Copyright Law of the United States of America (June 2003), circ 92.

Creative Commons: A Spectrum of Rights (n.d.). Retrieved

April 6, 2006, from

http://www.creativecommons.org/about/licenses/comics2

Creative Commons: Baseline rights and restrictions in all

licenses (n.d.). Retrieved on April 1, 2006 from

http://creativecommons.org/about/licenses/fullrights

Creative Commons: Creative Commons Licenses (n.d.).

Retrieved on April 1, 2006 from

http://creativecommons.org/about/licenses/meet-the-licenses

Creative Commons: Choosing a License (n.d.).

Retrieved on April 1, 2006 from

http://creativecommons.org/about/think

Creative Commons: Public Domain Dedication (n.d.).

Retrieved on April 11, 2006 from

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/publicdomain/

Creative Commons: Things to think about before you apply a

Creative Commons license to your work (n.d.).

Retrieved on April 1, 2006 from

http://creativecommons.org/about/licenses/index_html

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) (1998)

Eldred vs. Ashcroft, 537 U.S. (2003)

Lessig, L. (2002) Speech at the Creative Commons Launch. Retrieved April 1, 2006 from:

http://www.onlisareinsradar.com/archives/000782.php

Litman, J. (2001). Digital Copyright, Prometheus Books.

The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act (1998)

Rein, L. (2005) Copyright Basics for Web Designers (n.d.).

Retrieved April 1 from:

http://www.lisarein.com/seybold/

Rein, L. (2005) Songs From the Commons #4 (podcast)

Retrieved April 1, 2006:

http://www.mondoglobo.net/thecommons/?p=9

Schultz, J. (2006) Personal e-mail communication with Legal

Expert, April 8, 2006.

U.S. Constitution (year), Article I, Section 8 (1788)

Update April 13, 2006 - The link below goes to the final version. As I mentioned earlier, I hope that this table will continue to be a work in progress. Please let me know about your pros and cons.

Okay -- I've got a draft up of my

Creative Commons Pros and Cons table.

As Both An Idealist and a Skeptic

I'm only covering the main 6 licenses. But I'd like to keep adding to it after this initial publication.

Please email me at lisa@lisarein.com with any comments/suggestions/criticisms.

I leave for school tomorrow to turn things in around 3pm PST, so please, if you can, send me your comments by noon, that would be great.

I very much appreciate whatever time you have to look this over.

Again, non-expert feedback is also very much appreciated! This is supposed to be a guide for students of broadcasting, not law :-) I'd like to think it could be useful for anyone.

thanks!

Update April 13, 2006: The final guide is available Here.

I'm in the process of completing my final project for SFSU's Broadcast Electronic Communications Arts department (BECA) -- My assignment is to write a student licensing guide to help students with licensing their school productions.

It's most of the way complete except for a Pros and Cons table that I won't have ready for a few more hours.

A word file with the tracking turned on is available here:

http://video.lisarein.com/sfsu/guide/guide-4-11DFC.doc

A text file:

http://video.lisarein.com/sfsu/guide/guide-4-11-draft.txt

I'm including a text file here and in the "more" section below.

Please make changes directly to the file, or send me an email with suggestions about specific sections - please quote the text so I know what you're referring to.

This isn't about proofreading! This thing's already in pretty good shape. I'm wondering if it makes sense to experts and non-experts alike.

You do not need to be a legal expert to be helpful to me. I'm wondering if this stuff makes sense to newbies too. That's the whole point of this guide.

Please email me a lisa@lisarein.com with your comments and/or edited word file.

thanks!

lisa

BECA Student Licensing Guide - April 2006

By Lisa Rein, lisa@lisarein.com -

This draft has been replaced by the final version located here:

http://video.lisarein.com/sfsu/guide/finalguide4-12.txt

BECA Student Licensing Guide - April 2006

By Lisa Rein, lisa@lisarein.com

Introduction - Some background on copyright basics

Step 1 - Protecting yourself from getting sued.

Step 2 - Choosing a Creative Commons License for your own work.

Summary

The purpose of this guide is two-fold. The first goal is to teach you how to display your own mixed-media BECA productions publicly without fear of legal ramifications. (This will be accomplished by clearing all your content, creating it yourself, or using Creative Commons’ licensed content). The second goal is to teach you how to choose a Creative Commons license for your own productions, so that you may encourage their reuse while still protecting yourself from unauthorized uses.

Introduction - Some background on copyright basics

We're going to be talking specifically about Copyright in this manual. (Patents and trademarks, two other kinds of "intellectual property", have different guidelines and legal precedents.) Copyright protects the creators of artistic works (music, books, video, photography, you name it) from unauthorized use. For students who use copyrighted material in their academic productions, and later decide they'd like to show the work in other forums, using copyrighted material can become a minefield. When a student is just creating “neat stuff” in the classroom, music and video sources are a clear-cut case of “fair use.” However, should one of your productions come out good enough that you'd like to show it, display it, or broadcast it, traditional copyright rules will prohibit you from doing so. This is because public airing of productions containing the copyrighted work of others at film festivals, on television, or even on the Internet requires the explicit permission to the copyright holder in order to avoid legal and financial pitfalls.

The rules seem stricter for broadcast media because anything but a public-access TV show will make you sign a document stating that you have permission from the Copyright holder of every clip used in your production. Without this document, the TV station won't broadcast the content. On the Internet, this barrier of immediate broadcast is removed, but the laws remain the same. "Putting stuff up on the web" is easy to do with little or no effort, however, all of the laws prohibiting the unauthorized use of a Copyright holder's work are still in effect. You are simply publishing and distributing via the Web. Just because the physical act of “distribution” can take place without anyone's permission doesn't mean you won't be held accountable for it afterwards.

Copyright does not apply to the ”ideas” used within a “work”, only to the “work” itself: the article, the book, the movie, etc. Factual elements are not covered. For instance, if I wrote a book on the history of the San Francisco Earthquake, the facts I reported within the book would be in the public domain. So an artist can copyright their version of a historical account, but not the facts contained within that historical account. Likewise, you can reference numerous facts sourcing the original published work without getting any kind of permission. Such is the nature of research.

In order to adequately discuss alternate licensing options effectively, we must first define what "traditional copyright" means. "Traditional Copyright" refers all of the protections and restrictions as set forth in Copyright Law, based on all the numerous Copyright Acts that have been voted in by Congress up to the present. The original length of the Copyright term, set forth in The Copyright Act of 1790 by the Founding Fathers, lasted 14 years and was renewable once for a maximum length of 28 years. After that, the work went into the public domain, so others could use it and benefit from it. This Act also described what has come to be known as "the copyright bargain," in which copyright holders are allowed the exclusive right to make money from their work for this "limited time" of 14 or 28 years, after which the work went into the Public Domain for everyone to benefit from.

Unfortunately, the language used in the Constitution has been interpreted by some as implying that Congress has the power to determine what "limited" means. As a result, during the last 50 years, “limited” has been interpreted -and upheld by the Supreme Court in Eldred vs. Ashcroft in 2003 - to mean that Congress has the power to extend the length of this term. As a result, the Copyright term has been extended by Congress 11 times in the past 40 years: now the term runs 70 years past the death of the work’s creator or 95 years past the date of publication for a “work for hire"(where the creator has relinquished their copyright as part of the deal.)

What kinds of uses are not permitted based on preserving the rights of the Copyright holder?

If your production contains material covered under copyright, and you have not received the explicit permission of the copyright holder, you are not allowed to redistribute your production in any way to the public. It really limits your options.

As far as "reuse" goes, here are some examples. An individual can't make a copy of someone else's book and sell it. An individual can't take a book and make a movie out of it without the explicit permission of the copyright holder. In that case, someone might want to license the film rights. (A more common practice these days is to purchase an option to license the film rights at a future date for another, much larger sum.) In the case of reusing a photo that a person found on someone else's website, the situation gets complicated quickly. Just because the photo was found on a website doesn't mean that the website had proper permission to use it. Contacting the webmaster of the site doesn't always help locate the source of the media or the proper Copyright holder.

What are the differences between making a production for school, in which you can use or show copyrighted material to a school audience, and putting it on the Internet?

Well, there are “fair-use” provisions that allow you to use what you want within an academic environment. You are, in fact, violating the copyright holders' rights by using it without permission, but since it's only for a finite group of people in your classroom and you are not using the work for financial gain, such uses generally fall under “fair-use.” However, if the “work” is put on the Internet, this constitutes “public distribution.” When you place something on the Web, you are in effect publishing it and redistributing it. To a publisher, it seems as if you had bought a book at B. Dalton, made a large number of copies and gave them away for free.

Fair Use is too complicated and “gray” an area to cover in great detail, but the educational provisions that are specified by law are pretty simple. If you are commenting on a “work” in a non-commercial fashion, “fair use” allows you to republish parts of another work in order to make a scholarly or editorial point. The educational provisions of Title 17, Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976 are pretty straight forward, allowing people to reproduce "part or all of a work for purposes, such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research..." This is why you can always use whatever source material you need to for your class assignments.

Copyright Infringement

"Infringement" is violating a copyright-owner's exclusive rights. The law does not require that the infringer be aware they are doing so. Harm does not need to be proven. As an artist deciding whether or not to include pieces from the works of others, you want to make sure you're not infringing on any one else's rights, so you don't get sued.

What happens when you put something up on the Internet without permission and the Copyright holder finds out?

They can sue you for a lot of money, and make you destroy any copies of your work that contains the clip. The Copyright holder can demand that it be taken down pending investigation and, often, this will be done before you can defend yourself. Defending your “use” will happen after the fact. According to the DMCA, a Copyright holder need only have a "good faith belief" that his rights are being infringed to issue and "cease and desist" letter (a "c and d" or "takedown notice"). Even after you take the material down, you can still be charged anywhere from $5000 to $50,000 per violation. Defending yourself costs money, so having any sort of Copyright conflict at all can be expensive.

Step 1 - Protecting yourself from getting sued

The hard routes: Generating all original content or only showing other’s content in the classroom.

The "safest", albeit impractical, path to take is to create all of the pieces used in your “work” yourself. For example, when creating a video production, you’ll need to allow much more time to complete your production if you're also going to create an original soundtrack for it. You also need to be musically inclined, own your own production equipment, or have a lot of time and money and rent it. This scenario becomes quickly unrealistic.

If you are absolutely sure the video project is just a class assignment, and that you have no desire to put it on the Internet, play it on a cable access show, or submit it to a film festival or contest then, by all means, use what you want from whatever source you like.

As an artist and a producer, you may need to examine your readiness to lock up your creation in a vault and forget about it after it's done. Artists often don’t know for sure what they’re going to do with works once they're completed. At the very least, they may want to store a copy of it on their web-based portfolio. (Soon, all producers of media will be expected to have one of these. Already, at the time of this writing, a producer is definitely taken less seriously if they do not have any sort of web presence.)

Clear All Copyrighted Content or Use Creative Commons’ Licensed Content

So the first harsh, but easy to remember, rule of Copyright is don't use anything you find on the Internet or anywhere else without the explicit permission of the Copyright holder. Now this is easier said than done. It's sometimes very hard to reach the Copyright holder (a person or a corporate entity like a publishing house) and get permission to use the piece of music, art, journalism, etc. which the artist wants for their project. It’s especially frustrating when the copyrighted material is precisely what the artist needs to create a particular point or convey a particular message.

This situation creates two extreme responses for an individual wanting to use copyrighted material. The first response is for the individual to ask all Copyright holders to use their work (which might take months or years). The second response is for the individual to use whatever Copyrighted material they need and hope no one will object. This behavior might get the individual anything from a nasty “cease and desist” letter to a full-fledged lawsuit.

There is now a type of user “license” which attempts to circumnavigate the negative options often involved with traditional Copyright. With Creative Commons licenses, artists can assert, prior to usage of their material that, while retaining their existing rights as a copyright holder, they are also making their media available for certain educational or non-commercial uses.

Finding Creative Commons Licensed Content To Use

Playing it safe used to mean having less content to choose from. But now there are libraries of Creative Commons content that provide lots of nice alternatives for everything from music to backgrounds to stock photos to collage photography. When you use works licensed using one of their six basic licenses, you aren't restricted about what you can do with it when you're done. For a Creative Commons search engine, links to Creative Commons search features on Google and Yahoo, and links to over 20 libraries of Creative Commons content, visit:

http://www.creativecommons.org/find/

Step 2 - Choosing a Creative Commons License for your own work

For the purposes of this guide, we are going to assume that you either created the “media” yourself, obtained explicit permission from any Copyright holders to use all the media involved, or created your presentation using Creative Commons Licensed material that is pre-authorized for reuse.

Traditional Copyright protects the artist from abuse to such an extent that other students and artists may we be "afraid" to use their work for their soundtrack. If an artist *wants* to be used in non-commercial productions, they would use a CC license that allows those kinds of works without obtaining additional written permission. Eliminating this step saves hours of labor in the new artist’s production process. The new artist doesn’t have to go hunting around to obtain permission for the CC licensed work used within their own “work”, and other artist’s need not contact them to use their work.

When you choose a Creative Commons license or decide to just keep your media under traditional Copyright, what you are in effect doing is specifying rules for reuse; for example using music in a soundtrack for another’s video work, or sampling it within another song, etc. Your work is still completely protected under all existing Copyright, you are only loosening the reins on the specific uses outlined within whatever license you choose.

Note: Performing "covers" of songs, which is regulated under a compulsory license, demands payment but cannot disallow use. Sampling a song, on the other hand, and creating another musical work from it becomes a derivative work, which requires explicit permission from the Copyright holder of the sample.

Creative Commons’ Licenses in a Nutshell: One Given and Three Options

Here are some questions you can ask yourself when choosing a license for your productions. When deciding on a license, you are basically answering the question: "After someone downloads my media from the Internet into their computer to play it, what else can they do with it?"

All Creative Commons Licenses can be summarized as basically one given (attribution) and three options, for which you must decide "yes" or "no" (commercial use, derivatives, share-alike).

Attribution is a minimum requirement of all Creative Commons Licenses. They have to give you Attribution for using the work. That means they have to include your name in the credits and, preferably, include a link back to the page about your work.

Three Options:

1) Commercial use. - Can they download your work and resell it?

2) Derivative works - Can they remix it, alter it, and republish it?

3) If they are allowed to make derivative works, must those derivative works be licensed under the same CC license as yours?

All Creative Commons licenses require attribution. After that, you have two options: allowing/disallowing commercial usage and allowing/disallowing derivative works. Furthermore, if you do allow your work to be remixed to create another "derivative work," you may optionally require that such works be released under the same license as yours. This way, remixes of your work are also available to remix, rather than being "locked up" under another license. This "share-alike" provision embodies the true spirit of Creative Commons: creating a voluntary Public Domain in response to the ongoing loss of the "real" Public Domain due to the perpetual length of the copyright term. However, many people don't want to place any restrictions on reuse, fearing that such restrictions may serve as a deterrent to usage. (See Pros and Cons of CC licenses table.)

Creative Commons’ licenses work backwards from existing copyright to enable you to make exceptions to the normal copyright rule, and allow the uses you want without losing any of the "automatic" protections of "traditional copyright." Every license allows the work to be copied and distributed in any format, displayed or performed publicly, or webcast (a "digital public performance"). Every license applies world-wide and is irrevocable. If that "irrevocable" part sounds scary, fear not. Another feature of Creative Commons’ licenses is that they are non-exclusive. So putting your work out under a CC license can never interfere with anything else you choose to do with that work in the future.

The most restrictive license, and perhaps the "safest" to use until you have more time to understand the different options, is the "Attribution, Non-commercial, No-derivs" license. This license requires attribution, as do all Creative Commons licenses, allows usage in only non-commercial environments (schools, non-profits, students, and, potentially, a person's personal website), and requires that the work be included in its entirety. This doesn't mean that you have to use the whole song, but that whatever part you use is used “verbatim”, and is not altered or remixed to create another "derivative" work.

You can also use a Creative Commons License to put your work straight into the Public Domain. In doing so, you relinquish your copyright, and no one is required to give you attribution or acknowledgement of any kind. Placing a work directly into the Public Domain is more of a “statement” than anything else. It makes people take notice and see that you are serious about trying to preserve culture, art, and history. I wouldn't recommend doing anything like that until you have a clear understanding of everything discussed in this guide. You are guaranteed that more people will use your work if you place it into the Public Domain. That much is certain. It will take more time to analyze the effects of going direct to Public Domain before we can expand on the pros and cons of doing so.

All Rights Reserved Traditional Copyright

Some Rights Reserved Creative Commons

No Rights Reserved Public Domain

See the attached pros and cons table for a quick breakdown of the six main Creative Commons licenses. A version of this table with a direct link to a page where you can grab the HTML code needed to implement each license is available here:

http://www.lisarein.com/sfsu/creativecommons/prosandcons.html

Feel free to email me with any questions you may have at lisa@lisarein.com.

Good luck!

Wow. I can't believe I never posted my

Songs From The Commons show (#12). (Let's just say I'm busier than I think I've ever been in my entire life, doubled. )

But still. How could I have forgotten to tell you about it, after all that work? It took me a long time and I remember feeling good about it when it was done, although right now I'm consumed by too many things to remember why...

Oh yeah, it has my remix of Mc Jack In The Box's remix of Brad Sucks in it, for one thing. I was also pleased with how well Cindy Sheehan and friends' protesting at the UN was adapted to a beat.

The subject is recent developments in Creative Commons search tools:

1. http://creativecommons.org/find/

The CC folks threw a user interface on top of the google and yahoo searches.

It's also a great place to see a lot of great CC repositories all in one place.2. Flickr's Creative Commons Page

http://www.flickr.com/creativecommons/

Browse by license on this popular photography site.

3. Google's Advanced search feature:

http://www.google.com/advanced_search?hl=enAcross from the heading "Usage Rights," you will wee a drop down selector.

Update: So I just pulled this track from the cc mixter website because I used samples from PBS NOW that I did not create myself. And although I believe that it is my fair use to use them, and for others to use them, it is an indisputably gray area, and therefore does not belong on CC Mixter, where everyone knows that reuse is free and clear. Fair enough :-)

Here's the new link:

Borrow and Take2 - Colin Powell WMD Hoax Remix

This adds a "vocal" track from Colin Powell, Lawrence Wilkerson and David Brancaccio (PBS-NOW) over the top of Ashwan's Borrow and Take2

The Colin Powell WMD Hoax Remix part comes from a PBS NOW show located here:

http://video.lisarein.com/pbs/now/feb2006/02-03-06/

The sound clips are from this episode of NOW on PBS: http://www.pbs.org/now/thisweek/index_020306.html

software/hardware: TIVO, Canon GL-2, dual G4 mac, itunes, protools

samples i used:

I believe it was my fair use to use the sound samples from the PBS Now program detailing Larry Wilkerson's recount of the day's events during Powell's speech to the United Nations Security Council.

The video clips and MP3s are here:

http://video.lisarein.com/pbs/now/feb2006/02-03-06/

I used my tivo to capture NOW and then my camera to capture the video from my tivo via the analog hole. Then I used itunes to generate an mp3 from the .mov file, and imported that into protools, along with ASHWAN's track, to create the first part of this track, which is my remix. (The rest of the track after Colin Powell stops talking is the same as the ASHWAN version.)

More:

The sound clips are from this episode of NOW on PBS.

This uses the clips from NOW with David Brancaccio that interviews Larry Wilkerson, Colin Powell's ex Chief of Staff, about how he and Colin played into the hands of the Shrub Administration when they unwittingly "participated in a hoax on the American People, the International Community, and the United Nations Security Council."

Finally finished my latest

Songs From The Commons #11.

This one includes a Colin Powell WMD Hoax remix of Ashwan's

Borrow and Take 2, courtesy of yours truly. It's not available yet as a single on CC Mixter, but it will be soon.

It also has a cool remix by MC Jack In The Box of the Brad Sucks source files for "Work Out Fine."

I'm really starting to dig doing these shows.

I'm also writing a lot of my own music lately, and can't wait to finish my Masters in April, so I can get on with recording it...

The Colin Powell WMD Hoax files are from a NOW show that aired 2/3/06 - Video files and MP3s are located here.

A proper blog post is forthcoming...

I've been so busy I forgot to let you know that I put up a new show last week:

Show 10

This one features a new track from cdk and a vocal remix I created of hepepe's "Byrd of Cool."

Hope you like it!

This went up Tuesday, Dec 13, 2005.

Songs From The Commons #8

Lots of great music from teru's website -- including a mix from teru himself of a mashup of two other remixes.

This One’s For Tookie WilliamsNo Business As Usual This Show - A Man Imprisoned by the State of California Has Been Put To Death By that same state, and I just want to take a moment to think about it.

It happened around 12:30 am this morning- Dec 13, 2006. I don’t like to be reminded that we’re living in a police state, but things like state-sanctioned executions make it all too crystal clear.

Will we find out months or years from now that Tookie was innocent? We’re learning that innocent people are convicted all the time. It could happen to you or me, but research has proven definitively that it’s much more likely to happen to you if your an african american male.

And what if he was guilty after all? Is he arguably rehabilitated? Or is rehabilitation just a lie?

However you slice it, it leaves me sad. And thinking.

Whether you’re for or against the death penalty, I think you will agree that it’s important that we all think long and hard about what happened today.

This show just went up today:

Why Grokster Shouldn't Be Any More Responsible For When It Is Misused Than Smith And Wesson

As always there is a vocal and music only version available...

Update 12/5/05 3:16pm - I had a link to my old show until now. so sorry about that!

Here's the w/vocals version and the music only version.

This show takes a shot at explaining the similarities between the landmark Universal vs. Sony (Betamax) case of 1984 and the current MGM vs. Grokster case that went in front of the Supreme Court last summer.

I only touch upon it briefly in my show. There's a more complete explanation on the website.

The point then, and now, is that, historically, in this country, we choose to criminalize the misuse of a technology, rather than criminalizing the technology itself. Guns, for example, are only made for killing. Killing and maybe target practice. It's what they do. Depending on the circumstances surrounding when the killing takes place, such killing is legal or not. But do we hold gun manufacturers responsible for when gun technology is misused? Of course not. The concept is comical. In fact, legislation was recently passed to protect gun manufacturers from such liability. According to White House Press Secretary Scott McClellan, even President Bush "believes that the manufacturer of a legal product should not be held liable for the criminal misuse of that product by others."Unfortunately, when the Supreme's had a chance to decide MGM vs. Grokster on these grounds, it chose to do something else - to avoid these issues entirely, and create a new kind of indirect infringement: active inducement. Active Inducement takes place if someone intends to make another person infringe and then takes active steps to encourage it.

The court basically said there were two types before (contributory and vicarious) and now there's a new, third kind, called "inducement." That's what the court sent back to the Central District of California Court (9th Circuit) to determine if the defendants were actively inducing infringement.

So there used to be just two kinds of "indirect" infringement, vicarious and contributory.

"Vicarious" is when you're supervising people and making money from it, like at the Flea Market, if the owners of the Flea Market knew that stolen goods were being sold there. (A CA court ruled that Napster did this.)"Contributory" infringement is where you're supplying the means with knowledge that it will be used illegally. Like if I rented a bunch of CD burners to a bootleger and knew what he was going to do with them. Now, after Grokster, there's a third, where I intend to make you infringe and take active steps to encourage it. That's the test laid out by the decision...

Note: Although there was a development last week in MGM vs. Grokster, where Grokster settled, agreed to shut down, and agreed to pay $59 million in damages, Grokster was not the only named defendant in the case. StreamCast, Sharman Networks (distributor of Kazaa), and the founders of Kazaa are still in litigation.

Here is the full text of the article in case the link goes bad:

http://www.mondoglobo.net/thecommons/?p=11

A Better Introduction to Grokster - A Modern Day Sony Betamax Case

In this week's installation of The Grokster Chronicles, I will explain how the Grokster case is really just a modern day revisiting of the principles of the historical Betamax case. The "Betamax" case refers to Universal vs. Sony, in which the Supreme Court decided that a company was not liable for creating a technology that some customers may use for copyright infringing purposes, so long as the technology is capable of substantial non-infringing uses. Said another way, the court decided that, when a technology has many uses, the public cannot be denied the lawful uses just because some (or many or most) may use the product to infringe copyrights.

{{{MP3}}}

{{{MP3}}}

The court weighed the substantially positive noninfringing fair use right of a family being able to timeshift a program and watch it together later against the potential misuse of a person making 300 copies of the television program and selling them (piracy). Keeping this definition in mind, it becomes easier to understand how such judgements clearly apply to the Grokster case. Within the millions of files traded over a Kazaa-based P2P network, some infringe, while others clearly do not.

The point then, and now, is that, historically, in this country, we choose to criminalize the misuse of a technology, rather than criminalizing the technology itself. Guns, for example, are only made for killing. Killing and maybe target practice. It's what they do. Depending on the circumstances surrounding when the killing takes place, such killing is legal or not. But do we hold gun manufacturers responsible for when gun technology is misused? Of course not. The concept is comical. In fact, legislation was recently passed to protect gun manufacturers from such liability. According to White House Press Secretary Scott McClellan, even President Bush "believes that the manufacturer of a legal product should not be held liable for the criminal misuse of that product by others."

Unfortunately, when the Supreme's had a chance to decide MGM vs. Grokster on these grounds, it chose to do something else - to avoid these issues entirely, and create a new kind of indirect infringement: active inducement. Active Inducement takes place if someone intends to make another person infringe and then takes active steps to encourage it.

The court basically said there were two types before (contributory and vicarious) and now there's a new, third kind, called "inducement." That's what the court sent back to the Central District of California Court (9th Circuit) to determine if the defendants were actively inducing infringement.

So there used to be just two kinds of "indirect" infringement, vicarious and contributory.

"Vicarious" is when you're supervising people and making money from it, like at the Flea Market, if the owners of the Flea Market knew that stolen goods were being sold there. (A CA court ruled that Napster did this.)

"Contributory" infringement is where you're supplying the means with knowledge that it will be used illegally. Like if I rented a bunch of CD burners to a bootleger and knew what he was going to do with them. Now, after Grokster, there's a third, where I intend to make you infringe and take active steps to encourage it. That's the test laid out by the decision.

The trouble with the supremes defining a new type of indirect infringement is that it leaves the questions of "vicarious" and "contributory" infringement wide open, as well as the test of "substantial non-infringing uses" given to us in the Betamax decision. (So no one knows what the rule would have been on those.)

The opinion also contained two "concurrences." What are concurrences? Well, in a formal ruling, there is a majority opinion which lays down the law. It includes what is called a "holding" -- what the court held the law to be. Then there are secondary opinions included in the ruling when judges want to add commentary. They are either "concurrences" (which agree with the holding but perhaps for different or additional reasons) or "dissents" (which disagree with the holding and reasoning of the majority).

Typically, with concurrences, they are sections that the majority didn't support. In Grokster, you had the majority 9-0 but each concurrence only had 3 votes. If either had gotten 5 votes, it would have been part of the majority. Although these two concurrences conflict with each other, the judges writing them agreed generally on the opinion (unanimously in fact).

So, for the two concurrences that received three votes each, one said that the Sony Betamax test of "substantial non-infringing uses" was more than satisfied. The other said that Sony should be revisited and overturned.

So you may say "well, it would certainly be hard to prove that, until you look at the decision a bit closer. In Grokster, the supreme court said that even using the name "-ster" as in Grokster showed intent to induce infringement, because it was similar to Napster.

The tech community knows that "ster" doesn't have this kind of meaning at all. It's more like a name for doing fun things -- Friendster, a social network and Feedster, and RSS syndication feed service, certainly have nothing to do with contributory copyright infringement. Google's Gmail even uses "ster" as their default name suggestion when someone tries to get an email address and their name on its own is taken, rather than applying a number to the end.

This kind of confusion about technology and computer culture means it will be easier to sue companies and imply that they are encouraging people. Then its costly to defend -- because you're going to have to go to trial every time, costing you millions. You may win eventually, but who cares by then, because you're out of business.

And what does this mean to the average consumer? It means that you're not going to get as much new cool technology, and when you do get it, it's going to cost you more because of the added legal risks now associated with software development in general.

Note: Although there was a development last week in MGM vs. Grokster, where Grokster settled, agreed to shut down, and agreed to pay $59 million in damages, Grokster was not the only named defendant in the case. StreamCast, Sharman Networks (distributor of Kazaa), and the founders of Kazaa are still in litigation.

Special Thanks to Jason Schultz at the EFF for double checking the technical accuracy of my legal analysis.

Songs

1.

Slipping Away v. 2.0 Studio

by Lisa Rein.

http://www.lisarein.com/slippingaway2.0.html

Available under an Attribution 1.0:

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/1.0/

2.

one moment (cdk play it cool mix)

by cdk

http://ccmixter.org/media/files/cdk/2884

Available under the: Attribution Non-commercial Share Alike v 2.5 license:

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/

uses samples from:

midnight bliss dub samples by cdk

Moment of Green by Antony Raijekov

Blues and misc by Burnshee Thornside

3.

"Wake Up" from The Time is Now

by Inna Crisis

http://www.jamendo.com/album/352/

Attribution Non-commercial Share Alike v. 2.0:

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/

4. Theme Song to this show - “Unison” by dissent - from the upcoming Primal Deconstruction CD/LP. The track and an in has been pre-released by Wide Hive Records under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-commercial-No Derivs license. http://www.widehive.com/unison.html

5.

Patrick Fitzgerald Announcing the Scooter Libby Indictments

Scoop

http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/HL0510/S00315.htm

Resources

1. EFF's page on the Grokster case:

http://www.eff.org/IP/P2P/MGM_v_Grokster/

2. EFF's page on the Betamax case:

http://www.eff.org/legal/cases/betamax/

3.

Shoot someone? Not Smith & Wesson's fault. Copy a movie? Grokster's fault.

by RadicalRuss for the Daily Kos.

http://www.dailykos.com/story/2005/7/26/2160/13925

I just uploaded my fifth SFTC podcast.

This show features tracks from Wired's Creative Commons CD DJ Dolores, Dan The Automator, The Beastie Beastie Boys, and Thievery Corporation. Everything is available under CC's Sampling Plus License.

More music, less talk, this show. And starting next week, all of these shows will be available in a "yapping free" format. I'm doing this because, it seems to me, that after you hear the spoken portion once or twice, you'd probably be done with it. While a music-only version can live on in your Ipod...FOREVER! (crescendo...echo...fade out...)

I just uploaded a new Songs From The Commons podcast.

Lots of great music and some basic information on Creative Commons Licenses.

Enjoy!

My cc mixter page is up now.

I've uploaded my first track, Maybe We Can All Do Something, which features Craig Newmark and Fourstones. It's from my last podcast for Mondoglobo.net.

I've been getting a lot of stuff for my show from cc mixter. It's just a great site!

Hey! My new

Songs From The Commons podcast is up.

Please check it out :-)

I'm pre-releasing my first mix single that I've created from CC-licensed stuff.

This clip mixes "My Name Is Geoff" by Fourstones with Craig Newmark's Creative Commons Launch Speech.

I'm calling it

"Maybe We Can All Do Something."

It will be released under an Attribution-Non-commercial-Sharealike license when it's released. (So consider this version under that license for now.)

Bear in mind that this isn't Craig's speech as it was originally delivered. I've edited it together into versus and a chorus so it sounds cool with the music, but I don't believe I changed the meaning of what he was saying in the slightest.

Hope you like it. Let me know how the mix plays back on your various devices. I might remix before release if it's necessary. It's mixed now for my next

Songs From The Commons podcast, which goes up in the am.

My Second show is up.

Direct link to MP3

My first

Songs From The Commons show is up. Check it out.

Everything in the show (music and spoken word) is licensed under a Creative Commons license.

I'm trying to cover just the most basics of Copyright Law in these first two shows...Then we'll start talking about cases...

Hope you like it.

I'm producing a new weekly podcast for RU Sirius' new venture, Mondo Globo. The focus will be a combination of Copyright developments and Creative Commons licensed works.

I've been fishing around all the directories for good stuff, and I've found a few gems, but it's slow moving listening to every track one by one.

Then I remembered that I should ask you to send me links to CC-licensed stuff you already know is good.

Hand it over! :-)

Okay thanks,

lisa

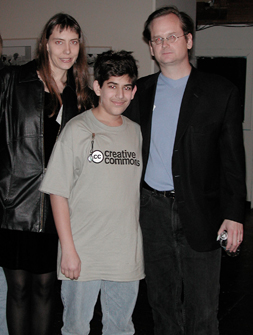

This is footage of Craig Newmark playing with Lawrence Lessig's son, Willem, while in the arms of Justin Hall. (As filmed by me.)

Hey these aren't prepared to stream over the Internet - you'll have to download them to your hard drive!

The "complete" version also has some shots of the party.

This footage was pretty dark so I had to lighten it in Premiere to make it watchable.

Highlights include Craig flapping his arms like a chicken (part 1)!!

Craig and Willem 1 of 2 (Small - 9 MB)

Craig and Willem 2 of 2 (Small - 9 MB)

Craig and Willem and Party - Complete Clip (Small - 32 MB)

Slightly higher res version of same clip (Small - 44 MB)

Here are links -- sorry no pictures!

Announcement from Adobe (Small - 4 MB)

Lessig 1 of 4 (Small - 16 MB)

Lessig 2 of 4 (Small - 11 MB)

Lessig 3 of 4 (Small - 12 MB)

Lessig 4 of 4 (Small - 13 MB)

Lessig - All (Small - 51 MB)

Neeru's Speech (Small - 7 MB)

Neeru's speech has a lot of great statistics in it explaining ' progress over the last year!

Here's a great interview with Jerry Goldman, Professor of Political Science at Northwestern on the Creative Commons site.

Jerry Goldman is determined to archive every recorded oral argument and bench statement in the Supreme Court since 1955, when the Court began to tape-record its public proceedings. Goldman, a professor of political science at Northwestern, founded the OYEZ Project in 1989 "to create and share a complete and authoritative archive of Supreme Court audio." This month the OYEZ mission takes a new step forward with the release of hundreds of hours of MP3 versions of their archived audio under a Creative Commons license.

Here is the full text of the interview in case the link goes bad:

http://creativecommons.org/learn/features/oyez

Jerry Goldman

Interview by Laura Lynch

Photo by Dennis Glenn

June 2003

Jerry Goldman is determined to archive every recorded oral argument and bench statement in the Supreme Court since 1955, when the Court began to tape-record its public proceedings. Goldman, a professor of political science at Northwestern, founded the OYEZ Project in 1989 "to create and share a complete and authoritative archive of Supreme Court audio." This month the OYEZ mission takes a new step forward with the release of hundreds of hours of MP3 versions of their archived audio under a Creative Commons license.

We spoke with Jerry recently about The OYEZ Project, their use of Creative Commons licenses, and the impact of their new MP3 release.

CC: What inspired you to create The OYEZ Project?

Jerry Goldman: In the late 1980s Professor Linda Kerber gave a talk at Northwestern University on her project dealing with gender discrimination in the law. Kerber played a few audio excerpts from the oral arguments in Hoyt v. Florida, a case that upheld the exemption of women from jury service. The audio was enlightening because it opened up a new way of thinking about the Court and grasping its work. It was my view that technology could enable a better use of these materials.

A later demonstration of such technology was equally inspiring. Two English professors visited Northwestern to discuss their Shakespeare project. Using an early Mac, a video-laser disc player, a color monitor, and some speakers, they demonstrated how one could highlight, say, Act II Scene 3 from Macbeth and then instantly play back the corresponding video. The ability to integrate text, audio, and video lay the groundwork for future OYEZ projects involving audio and annotation tools.

CC: After you became interested in the Court's audio recordings, how did The OYEZ Project begin?

JG: The earliest version of The OYEZ Project dates back to 1989. I came up with the idea of presenting our Supreme Court data and archives like a baseball card collection while sitting at a Chicago Cubs game at Wrigley Field. The idea materialized into a pre-web version consisting of complex HyperCard stacks. The stacks contained an elementary demonstration of video and audio linked to background information on the individual justices and the cases they decided. As a tribute to OYEZ's origin we created the "Law-Baseball Quiz," an idea from the creative mind of the late law professor, Robert Cover.

The transition to downloadable MP3s is a result of working with Chris Karr, a creative and forward-thinking computer scientist and web architect. Chris made me wake up to the need for wider sharing of our materials. I'm greatly indebted to him and quite pleased to acknowledge his contribution to the Creative Commons effort and to the entire re-conceptualization of The OYEZ Project.

CC: How did you obtain the Supreme Court audio materials? Why have you decided to release them?

JG: We purchased and collected the audio from the National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Maryland. The audio materials — principally in the form of oral arguments — are the core of The OYEZ Project.

We released the public proceedings because they are some of the greatest intellectual and legal debates of our era. Transcripts — even with the justices identified — lack the emotive qualities of humor, irony and anger, which audio conveys. The first Roe v. Wade argument (the case was reargued) stands out in my mind. When Jay Floyd, representing the state of Texas, began his argument, he tried a bit of good-ole-boy humor, which was met by the Court's silence. (Remember that the bench was all men in the early 1970s.) His argument headed downhill from there. Sarah Weddington, representing Jane Roe, made a kitchen-sink argument, throwing every thing she could imagine at the Court. That struck me as pointless, though some of the justices were very gentle about it. Among the announcements of opinions, the Regents v. Bakke audio stands out. In a rare exercise, the justices spoke at length about their disagreements in the case, and the emotions are palpable.

CC: Government works are essentially uncopyrightable. How did you obtain the copyright for these works?

JG: The OYEZ audio is a derivative work because we've made technical and editorial judgments that depart from the original source. The raw audio we obtain from the National Archives often needs to be edited. Sometimes, the first part of an argument will exist on one reel and the remainder is on a second. We dub both reels and then match them up, removing any overlap. We have voice corrected many hours of audio because of timbre and pitch problems.

CC: How does this MP3 release add to what OYEZ is offering currently? What good might come of this for OYEZ in the future?

JG: It offers new independence to users by permitting downloads of OYEZ audio and promoting the sharing of those materials — subject to our Creative Commons license — on peer-to-peer networks. While we enjoy our popularity in academic and educational circles, we can reach more listeners by enabling downloadable versions. With the development of Creative Commons, we have, for the first time, a way to license our content that assures use consistent with our objectives.

The more I listen to the recordings the more I realize that the true value is not in the audio itself but in a community of dedicated listeners and scholars who could add to the audio. The original Court transcripts do not identify the justices, only the attorneys. Adding transcripts and voices to the audio would help create a searchable audio archive. For instance, you could search and listen to any audio where Scalia used the expression "strict scrutiny." Listeners could annotate audio by pinpointing selections that illustrate good and bad advocacy, or particularly interesting views on an issue, and then share their annotation findings with others in a shared community. Encouraging a community to select and identify audio clips will increase awareness of OYEZ audio as a primary source for scholarship and teaching.

CC: Why did you decide to use Creative Commons licenses? Why do you think this project is important?

JG: Creative Commons has a good solution to the nagging problem of commercialization and is based on a solid theory regarding the power of creativity. We want to contribute to that creative enterprise. It doesn't make sense to maintain the high transaction costs associated with acquiring these materials. Having made this investment — with the help of many institutions —it is our responsibility to freely share this treasure.

Peer-to-peer networking is getting a bad name as a result of the enormous amount of unlicensed music file-sharing. By making our collection available we are emphasizing a good use of P2P and hopefully inspiring other content creators to recognize that there is more to be gained by sharing than by withholding their work from the public.

We hope OYEZ audio will be used by law students, Supreme Court junkies, practicing attorneys, teachers, and the general public. To borrow from the immortal Yogi Berra: "You can hear a lot by listening." The experience is daunting and thrilling, and my hope is that by listening and learning, the quality of advocacy and communication will improve.

Creative Commons CTO Mike Linksvayer has announced that CC mp3 (and general "non-web") metadata guidelines are now linked to from the website and supported with additional material.

They've provided a cute little how-to to help you get started.

Welcome Joi!

Creative Commons Welcomes Joi Ito to Board of Directors

(Creative Commons Press Release)

Creative Commons, a nonprofit corporation dedicated to expanding the world of reusable content online, announced today that Joichi Ito has joined its Board of Directors. Ito is a venture capitalist, technologist, and internationally popular weblogger and commentator based in California and Japan."We are thrilled to have Joi Ito join the team," said Lawrence Lessig, chairman of Creative Commons and professor of law at Stanford University. "His unique breadth of experience in technology, business, and policy — and his well-earned reputation as an innovator on an international level — make him a perfect new colleague for our growing organization."

Here is the full text of the article in case the link goes bad:

http://creativecommons.org/press-releases/entry/3721

Creative Commons Welcomes Joi Ito to Board of Directors

Monday, June 16, 2003

San Francisco- and Tokyo-based venture capitalist, technologist, and policy expert joins leadership of the Silicon Valley nonprofit

Palo Alto, USA — Creative Commons, a nonprofit corporation dedicated to expanding the world of reusable content online, announced today that Joichi Ito has joined its Board of Directors. Ito is a venture capitalist, technologist, and internationally popular weblogger and commentator based in California and Japan.

"We are thrilled to have Joi Ito join the team," said Lawrence Lessig, chairman of Creative Commons and professor of law at Stanford University. "His unique breadth of experience in technology, business, and policy — and his well-earned reputation as an innovator on an international level — make him a perfect new colleague for our growing organization."

"Protecting the commons is essential for enabling emerging technologies and businesses in networked consumer electronics and the Internet," said Ito. "It is critical for Japan and the rest of the world to understand and embrace Creative Commons‚ principles and tools. I am honored to join this world-class organization to help make it happen."

Ito joins a Board of Directors that includes Lessig; fellow cyberlaw experts James Boyle, Michael Carroll, and Molly Shaffer Van Houweling; public domain web publisher Eric Eldred; filmmaker Davis Guggenheim; MIT computer science professor Hal Abelson; and lawyer-turned-documentary filmmaker-turned-cyberlawyer Eric Saltzman.

More about Joichi Ito

Joichi Ito is the founder and CEO of Neoteny, http://www.neoteny.com, a venture capital firm focused on personal communications and enabling technologies. He has created numerous Internet companies including PSINet Japan, Digital Garage and Infoseek Japan. In 1997 Time ranked him as a member of the CyberElite. In 2000 he was ranked among the "50 Stars of Asia" by Business Week and commended by the Japanese Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications for supporting the advancement of IT. In 2001 the World Economic Forum chose him as one of the 100 "Global Leaders of Tomorrow" for 2002.

More information at http://joi.ito.com.

More about Creative Commons

A nonprofit corporation, Creative Commons promotes the creative re-use of intellectual works — whether owned or public domain. It is sustained by the generous support of The Center for the Public Domain and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Creative Commons is based at Stanford Law School, where it shares staff, space, and inspiration with the school's Center for Internet and Society.

More information at http://creativecommons.org.

Contact

Glenn Otis Brown

Executive Director

Creative Commons

1.650.723.7572 (tel)

1.415.336.1433 (cell)

glenn -AT- creativecommons.org

Joichi Ito

jito -AT- neoteny.com

Neeru Paharia

Assistant Director

Creative Commons

1.650.724.3717 (tel)

1.510.823.1073 (cell)

neeru -AT- creativecommons.org

Craig Newmark at the Creative Commons Launch - 18 MB

Craig Newmark at the Creative Commons Launch - 10 MB