Saves us the trouble of having to do it through congress, I guess.

This new guy, Bob Gates, is another old guy that used to work for his dad, with CIA connections.

So it's not like there a new good guy coming in that's going to help us sort out the mess over in Iraq or anything.

I've been shaping up my library a bit. Going through old hard drives and making sure that I have uploaded things before I clear off my drive.

What I'm actually finding is a file or two I forgot to upload, or sets of video files I forgot to generate MP3s for. So...

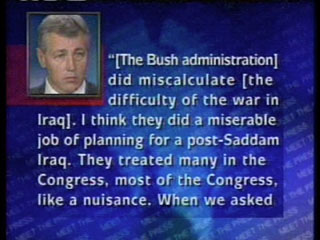

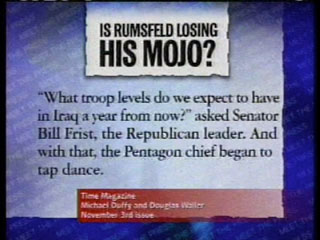

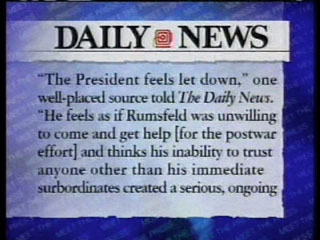

That's what I did today: generated MP3s of Rove and Rummy on Meet The Press:

Rummy on Meet The Press - February 6, 2005

Rummy MP3s (MP3s)

Rummy Videos (Videos)

Rove on Meet the Press - November 7, 2004

Rove MP3s

Rove Videos

This is from the February 6, 2005 program of Meet the Press.

Update 2/8/05: I've broken it down into 2 halfs, and made MP3s of it

I still have to break this down into smaller clips, but I wanted to make complete video and audio available for press folks and things that might need it asap.

Basically, Tim Russert is ruthless with the flinging of the fact.

Rummy loses it a couple time, although he quickly recovers. He admits that he may have "mis spoke" a couple times, and disregards those facts and figures that he wasn't prepared to respond to.

I will be putting up smaller clips and better analysis soon, promise.

For now, this stuff is here:

Video Of Rumsfeld On Meet The Press

Okay, so I'm having trouble posting because of all the traffic on the server -- which is GOOD, I suppose, except that it's making it hard for me to post.

(Don't worry! The video should play back fine, we bought a larger pipe this week just for the occasion.)

So I'm just going to fight to get this post up for a while, with links to the directories of everything. And then I'll try to get the posts up one by one later today.

Frontline: Rumsfeld's War

(How Rumsfeld used the poor tactics that screwed up the military in Vietnam to screw up the military in Iraq. Really, except for, of course, the innocent people of Iraq who were killed/tortured by some of our troops, the rest of our troops are in the process of being screwed over worse than anybody right now.)

Frontline: The Choice 2004

(This chronicles the lives of Kerry and the Shrub from Yale on.)

Patrick Miller On 60 Minutes

The real hero of the Jessica Lynch story, and how the Shrub Administration actually covered up his heroism in order to peddle their false story about Jessica Lynch's rescue.

This is from the June 21, 2004 program.

Stewart: "Mr. Vice President, I have to inform you: You're pants are on fire."

Cheney said he never stated that it was "pretty well confirmed" that meetings had taken place between Saddam's Officials and Al Queda members. The Daily Show dug up the Meet the Press coverage from December 9, 2001 that proves otherwise.

As a blogger and "traditional" journalist, I always hesitate to throw the word "lie" around unless I can validate my statement. How wonderful that we live in an age where I can present my case and back it up with evidence all on one interactive medium (for those that have quicktime, anyway...)

I also had the luxury of having the Daily Show With Jon Stewart to do my homework for me.

Here's the Complete Video Clip of the contradicting statements as presented within this larger daily show clip. (The larger clip also contains footage of the Shrub and Rummy making excuses for their past inaccurate statements.)

Here'sa tiny clip of Cheney denying he ever said the meeting was "pretty well confirmed.

(Source: CNBC)

CNBC: "You have said in the past that it was quote "pretty well confirmed."

Cheney: "No, I never said that. Never said that. Absolutely not."

Here's a little clip of the Meet the Press footage

where he clearly did say just that such a meeting was "pretty well confirmed."

(Source: Meet The Press, December 9, 2001)

Cheney: "It's been pretty well confirmed, that he didn't go to Prague and he did meet with a Senior Official of the Iraqi Intelligence service."

The Daily Show (The best news on television.)

Michael Isikoff discovered

this Shrub Administration memo which outlines a policy of rejecting the Geneva Convention for War On Terror prisoners.

Here's the Newsweek story that got this all started:

Double Standard?.

This is a big deal guys, and Bill Moyers and Brian Brancaccio do their usual great job of explaining exactly why -- and within a historical context. Then Brian interviews Columbia Law School Professor Scott Horton about the frighting implications of this policy.

This is from the May 21, 2004 program of Bill Moyers Now.

Want to mirror these clips?? Let me know! (

Mirror 1 of the complete version.)

This first clip provides details of the memo and some historical context:

Moyers On The Shrub's Geneva-Rejection Policy - Part 1 of 3 (Small - 10 MB)

These next two clips contain an interview with Scott Horton where he analyses the Shrub's justifaction for a Geneva Convention "double standard":

Moyers On The Shrub's Geneva-Rejection Policy - Part 2 of 3

(Small - 14 MB)

Moyers On The Shrub's Geneva-Rejection Policy - Part 3 of 3

(Small - 14 MB)

Here's the whole thing in a huge 37 MB file

David Brancaccio talks to Scott Horton, President of the International League for Human Rights. Horton will discuss the legal basis for the global war on terror and the U.S. government classified memo that puts forth what NEWSWEEK described as "a legal framework to justify a secret system of detention and interrogation that sidesteps the historical safeguards of the Geneva Convention." Mr. Horton also recently spearheaded a Bar Association of New York report: "

Human rights standards applicable to the United States' interrogation of detainees."

More about Scott from his website:

Mr. Horton has been a lifelong activist in the human rights area, having served as counsel to Andrei Sakharov, Elena Bonner, Sergei Kovalev and other leaders of the Russian human rights and democracy movements for over twenty years and having worked with the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights and the International League for Human Rights, among other organizations. He is currently president of the International League and a director of the Moscow-based Andrei Sakharov Foundation. Mr. Horton is also an advisor of the Open Society Institute's Central Eurasia Project, and a director of the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law, the Council on Foreign Relations's Center for Preventive Action and numerous other NGO organizations.Mr. Horton is an adjunct professor at the Columbia University School of Law and the author of over 200 articles and monographs on legal developments in nations in transition.

This post goes with this footage from Bill Moyers Now

Double Standards?

A Justice Department memo proposes that the United States hold others accountable for international laws on detainees—but that Washington did not have to follow them itself

By

Michael Isikoff for Newsweek.

In a crucial memo written four months after the September 11, 2001, terror attacks, Justice Department lawyers advised that President George W. Bush and the U.S. military did not have to comply with any international laws in the handling of detainees in the war on terrorism. It was that conclusion, say some critics, that laid the groundwork for aggressive interrogation techniques that led to the abuses at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq.The draft memo, which drew sharp protest from the State Department, argued that the Geneva Conventions on the treatment of prisoners of war did not apply to any Taliban or Al Qaeda fighters being flown to the detention center at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, because Afghanistan was a “failed state” whose militia did not have any status under international treaties.

But the Jan. 9, 2002 memo, written by Justice lawyers John Yoo and Robert J. Delahunty, went far beyond that conclusion, explicitly arguing that no international laws—including the normally observed laws of war—applied to the United States at all because they did not have any status under federal law.

Here is the complete article in case the link goes bad:

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/5032094/site/newsweek/

WEB EXCLUSIVE

By Michael Isikoff

Investigative Correspondent

Newsweek

Updated: 1:42 p.m. ET May 22, 2004

May 21 - In a crucial memo written four months after the September 11, 2001, terror attacks, Justice Department lawyers advised that President George W. Bush and the U.S. military did not have to comply with any international laws in the handling of detainees in the war on terrorism. It was that conclusion, say some critics, that laid the groundwork for aggressive interrogation techniques that led to the abuses at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq.

The draft memo, which drew sharp protest from the State Department, argued that the Geneva Conventions on the treatment of prisoners of war did not apply to any Taliban or Al Qaeda fighters being flown to the detention center at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, because Afghanistan was a “failed state” whose militia did not have any status under international treaties.

But the Jan. 9, 2002 memo, written by Justice lawyers John Yoo and Robert J. Delahunty, went far beyond that conclusion, explicitly arguing that no international laws—including the normally observed laws of war—applied to the United States at all because they did not have any status under federal law.

“As a result, any customary international law of armed conflict in no way binds, as a legal matter, the President or the U.S. Armed Forces concerning the detention or trial of members of Al Qaeda and the Taliban,” according to a copy of the memo obtained by NEWSWEEK. A copy of the memo is being posted today on NEWSWEEK’s Web site.

More War Crimes Memos

• Read the complete Yoo-Delahunty memo:

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

• Read the memo on habeas jurisdiction

At the same time, and even more striking, according to critics, the memo explicitly proposed a de facto double standard in the war on terror in which the United States would hold others accountable for international laws it said it was not itself obligated to follow.

After concluding that the laws of war did not apply to the conduct of the U.S. military, the memo argued that President Bush could still put Al Qaeda and Taliban fighters on trial as war criminals for violating those same laws. While acknowledging that this may seem “at first glance, counter-intuitive,” the memo states this is a product of the president’s constitutional authority “to prosecute the war effectively.”

The two lawyers who drafted the memo, entitled “Application of Treaties and Laws to Al Qaeda and Taliban Detainees,” were key members of the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, a unit that provides legal advice to the White House and other executive-branch agencies. The lead author, John Yoo, a conservative law professor and expert on international law who was at the time deputy assistant attorney general in the office, also crafted a series of related memos—including one putting a highly restrictive interpretation on an international torture convention—that became the legal framework for many of the Bush administration’s post-9/11 policies. Yoo also coauthored another OLC memo entitled “Possible Habeas Jurisdiction Over Aliens Held in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba,” that concluded that U.S. courts could not review the treatment of prisoners at the base.

Critics say the memos’ disregard for the United States’ treaty obligations and international law paved the way for the Pentagon to use increasingly aggressive interrogation techniques at Guantanamo Bay—including sleep deprivation, use of forced stress positions and environmental manipulation—that eventually were applied to detainees at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. The customary laws of war, as articulated in multiple international treaties and conventions dating back centuries, also prohibit a wide range of conduct such as attacks on civilians or the murder of captured prisoners.

Kenneth Roth, the executive director of Human Rights Watch, who has examined the memo, described it as a “maliciously ideological or deceptive” document that simply ignored U.S. obligations under multiple international agreements. “You can’t pick or choose what laws you’re going to follow,” said Roth. “These political lawyers set the nation on a course that permitted the abusive interrogation techniques” that have been recently disclosed.

When you read the memo, “the first thing that comes to mind is that this is not a lofty statement of policy on behalf of the United States,” said Scott Horton, president of the International League for Human Rights, in an interview scheduled to be aired tonight on PBS’s “Now with Bill Moyers” show. “You get the impression very quickly that it is some very clever criminal defense lawyers trying to figure out how to weave and bob around the law and avoid its applications.”

More From Michael Isikoff

• Memos Reveal War Crimes Warnings

• Prison Scandal: Brooklyn's Version of Abu Ghraib?

At the time it was written, the memo also prompted a strong rebuttal from the State Department’s Legal Advisor’s office headed by William Howard Taft IV. In its own Jan. 11, 2002, response to the Justice draft, Taft’s office warned that any presidential actions that violated international law would “constitute a breach of an international legal obligation of the United States” and “subject the United States to adverse international consequences in political and legal fora and potentially in the domestic courts of foreign countries.”

“The United States has long accepted that customary international law imposes binding obligations as a matter of international law,” reads the State Department memo, which was also obtained by NEWSWEEK. “In domestic as well as international fora, we often invoke customary international law in articulating the rights and obligations of States, including the United States. We frequently appeal to customary international law.” The memo then cites numerous examples, ranging from the U.S. Army Field Manual on the Law of Land Warfare (“The unwritten or customary law of war is binding upon all nations,” it reads) to U.S. positions in international issues such as the Law of the Sea.

But the memo also singled out the potential problems the Justice Department position would have for the military tribunals that President Bush had recently authorized to try Al Qaeda members and suspected terrorists. Noting that White House counsel Alberto Gonzales had publicly declared that the persons tried in such commissions would be charged with “offenses against the international laws of war,” the State Department argued that the Justice position would undercut the basis for the trials.

“We are concerned that arguments by the United States to the effect that customary international law is not binding will be used by defendants before military commissions (or in proceedings in federal court) to argue that the commissions cannot properly try them for crimes under international law,” the State memo reads. “Although we can imagine distinctions that might be offered, our attempts to gain convictions before military commissions may be undermined by arguments which call into question the very corpus of law under which offenses are prosecuted.”

The Yoo-Delahunty memo was addressed to William J. Hanes, then general counsel to the Defense Department. But administration officials say it was the primary basis for a Jan. 25, 2002, memo by White House counsel Gonzales—which has also been posted on NEWSWEEK’s Web site—that urged the president to stick to his decision not to apply prisoner-of-war status under the Geneva Conventions to captured Al Qaeda or Taliban fighters. The president’s decision not to apply such status to the detainees was announced the following month, but the White House never publicly referred to the Justice conclusion that no international laws—including the usual laws of war—applied to the conflict.

FREE VIDEO

Launch

• Inside Abu Ghraib Prison

This video, provided by The Washington Post, shows U.S. soldiers with Abu Ghraib prisoners. The undated footage was said to have been shot last fall.

NEWSWEEK

One international legal scholar, Peter Spiro of Hofstra University, said that the conclusions in the memo related to international law “may be defensible” because most international laws are not binding in U.S. courts. But Spiro said that “technical” and “legalistic” argument does not change the effect that the United States still has obligations in international courts and under international treaties. “The United States is still bound by customary international law,” he said.

One former official involved in formulating Bush administration policy on the detainees acknowledged that there was a double standard built into the Justice Department position, which the official said was embraced, if not publicly endorsed, by the White House counsel’s office. The essence of the argument was, the official said, “it applies to them, but it doesn’t apply to us.”

But the official said this was an eminently defensible position because there were many categories of international law, some of which clearly could not be interpreted to be binding on the president. In any case, the general administration position of not applying any international standards to the treatment of detainees was driven by the paramount needs of preventing another terrorist attack. “The Department of Justice, the Department of Defense and the CIA were all in alignment that we had to have the flexibility to handle the detainees—and yes, interrogate them—in ways that would be effective,” the official said.

The Roots of Torture

The road to Abu Ghraib began after 9/11, when Washington wrote new rules to fight a new kind of war.

By John Barry, Michael Hirsh and Michael Isikoff for Newsweek International.

Indeed, the single most iconic image to come out of the abuse scandal - that of a hooded man standing naked on a box, arms outspread, with wires dangling from his fingers, toes and penis - may do a lot to undercut the administration's case that this was the work of a few criminal MPs. That's because the practice shown in that photo is an arcane torture method known only to veterans of the interrogation trade. "Was that something that [an MP] dreamed up by herself? Think again," says Darius Rejali, an expert on the use of torture by democracies. "That's a standard torture. It's called 'the Vietnam.' But it's not common knowledge. Ordinary American soldiers did this, but someone taught them."Who might have taught them? Almost certainly it was their superiors up the line. Some of the images from Abu Ghraib, like those of naked prisoners terrified by attack dogs or humiliated before grinning female guards, actually portray "stress and duress" techniques officially approved at the highest levels of the government for use against terrorist suspects. It is unlikely that President George W. Bush or senior officials ever knew of these specific techniques, and late last - week Defense spokesman Larry DiRita said that "no responsible official of the Department of Defense approved any program that could conceivably have been intended to result in such abuses." But a NEWSWEEK investigation shows that, as a means of pre-empting a repeat of 9/11, Bush, along with Defense Secretary Rumsfeld and Attorney General John Ashcroft, signed off on a secret system of detention and interrogation that opened the door to such methods. It was an approach that they adopted to sidestep the historical safeguards of the Geneva Conventions, which protect the rights of detainees and prisoners of war. In doing so, they overrode the objections of Secretary of State Colin Powell and America's top military lawyers - and they left underlings to sweat the details of what actually happened to prisoners in these lawless places. While no one deliberately authorized outright torture, these techniques entailed a systematic softening up of prisoners through isolation, privations, insults, threats and humiliation - methods that the Red Cross concluded were "tantamount to torture."

The Bush administration created a bold legal framework to justify this system of interrogation, according to internal government memos obtained by NEWSWEEK. What started as a carefully thought-out, if aggressive, policy of interrogation in a covert war - designed mainly for use by a handful of CIA professionals - evolved into ever-more ungoverned tactics that ended up in the hands of untrained MPs in a big, hot war. Originally, Geneva Conventions protections were stripped only from Qaeda and Taliban prisoners. But later Rumsfeld himself, impressed by the success of techniques used against Qaeda suspects at Guantanamo Bay, seemingly set in motion a process that led to their use in Iraq, even though that war was supposed to have been governed by the Geneva Conventions. Ultimately, reservist MPs, like those at Abu Ghraib, were drawn into a system in which fear and humiliation were used to break prisoners' resistance to interrogation.

Here is the full text of the article in case the link goes bad:

http://msnbc.msn.com/id/4989481/

also at truthout:

http://www.truthout.org/docs_04/051804C.shtml

The Roots of Torture

By John Barry, Michael Hirsh and Michael Isikoff

Newsweek International

May 24 Issue

The road to Abu Ghraib began after 9/11, when Washington wrote new rules to fight a new kind of war.

May 24 - It's not easy to get a member of Congress to stop talking. Much less a room full of them. But as a small group of legislators watched the images flash by in a small, darkened hearing room in the Rayburn Building last week, a sickened silence descended. There were 1,800 slides and several videos, and the show went on for three hours. The nightmarish images showed American soldiers at Abu Ghraib Prison forcing Iraqis to masturbate. American soldiers sexually assaulting Iraqis with chemical light sticks. American soldiers laughing over dead Iraqis whose bodies had been abused and mutilated. There was simply nothing to say. "It was a very subdued walk back to the House floor," said Rep. Jane Harman, the ranking Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee. "People were ashen."

The White House put up three soldiers for court-martial, saying the pictures were all the work of a few bad-apple MPs who were poorly supervised. But evidence was mounting that the furor was only going to grow and probably sink some prominent careers in the process. Senate Armed Services Committee chairman John Warner declared the pictures were the worst "military misconduct" he'd seen in 60 years, and he planned more hearings. Republicans on Capitol Hill were notably reluctant to back Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. And NEWSWEEK has learned that U.S. soldiers and CIA operatives could be accused of war crimes. Among the possible charges: homicide involving deaths during interrogations. "The photos clearly demonstrate to me the level of prisoner abuse and mistreatment went far beyond what I expected, and certainly involved more than six or seven MPs," said GOP Sen. Lindsey Graham, a former military prosecutor. He added: "It seems to have been planned."

Indeed, the single most iconic image to come out of the abuse scandal - that of a hooded man standing naked on a box, arms outspread, with wires dangling from his fingers, toes and penis - may do a lot to undercut the administration's case that this was the work of a few criminal MPs. That's because the practice shown in that photo is an arcane torture method known only to veterans of the interrogation trade. "Was that something that [an MP] dreamed up by herself? Think again," says Darius Rejali, an expert on the use of torture by democracies. "That's a standard torture. It's called 'the Vietnam.' But it's not common knowledge. Ordinary American soldiers did this, but someone taught them."

Who might have taught them? Almost certainly it was their superiors up the line. Some of the images from Abu Ghraib, like those of naked prisoners terrified by attack dogs or humiliated before grinning female guards, actually portray "stress and duress" techniques officially approved at the highest levels of the government for use against terrorist suspects. It is unlikely that President George W. Bush or senior officials ever knew of these specific techniques, and late last - week Defense spokesman Larry DiRita said that "no responsible official of the Department of Defense approved any program that could conceivably have been intended to result in such abuses." But a NEWSWEEK investigation shows that, as a means of pre-empting a repeat of 9/11, Bush, along with Defense Secretary Rumsfeld and Attorney General John Ashcroft, signed off on a secret system of detention and interrogation that opened the door to such methods. It was an approach that they adopted to sidestep the historical safeguards of the Geneva Conventions, which protect the rights of detainees and prisoners of war. In doing so, they overrode the objections of Secretary of State Colin Powell and America's top military lawyers - and they left underlings to sweat the details of what actually happened to prisoners in these lawless places. While no one deliberately authorized outright torture, these techniques entailed a systematic softening up of prisoners through isolation, privations, insults, threats and humiliation - methods that the Red Cross concluded were "tantamount to torture."

The Bush administration created a bold legal framework to justify this system of interrogation, according to internal government memos obtained by NEWSWEEK. What started as a carefully thought-out, if aggressive, policy of interrogation in a covert war - designed mainly for use by a handful of CIA professionals - evolved into ever-more ungoverned tactics that ended up in the hands of untrained MPs in a big, hot war. Originally, Geneva Conventions protections were stripped only from Qaeda and Taliban prisoners. But later Rumsfeld himself, impressed by the success of techniques used against Qaeda suspects at Guantanamo Bay, seemingly set in motion a process that led to their use in Iraq, even though that war was supposed to have been governed by the Geneva Conventions. Ultimately, reservist MPs, like those at Abu Ghraib, were drawn into a system in which fear and humiliation were used to break prisoners' resistance to interrogation.

"There was a before-9/11 and an after-9/11," as Cofer Black, the onetime director of the CIA's counterterrorist unit, put it in testimony to Congress in early 2002. "After 9/11 the gloves came off." Many Americans thrilled to the martial rhetoric at the time, and agreed that Al Qaeda could not be fought according to traditional rules. But it is only now that we are learning what, precisely, it meant to take the gloves off.

The story begins in the months after September 11, when a small band of conservative lawyers within the Bush administration staked out a forward-leaning legal position. The attacks by Al Qaeda on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, these lawyers said, had plunged the country into a new kind of war. It was a conflict against a vast, outlaw, international enemy in which the rules of war, international treaties and even the Geneva Conventions did not apply. These positions were laid out in secret legal opinions drafted by lawyers from the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel, and then endorsed by the Department of Defense and ultimately by White House counsel Alberto Gonzales, according to copies of the opinions and other internal legal memos obtained by NEWSWEEK.

The Bush administration's emerging approach was that America's enemies in this war were "unlawful" combatants without rights. One Justice Department memo, written for the CIA late in the fall of 2001, put an extremely narrow interpretation on the international anti-torture convention, allowing the agency to use a whole range of techniques - including sleep deprivation, the use of phobias and the deployment of "stress factors" - in interrogating Qaeda suspects. The only clear prohibition was "causing severe physical or mental pain" - a subjective judgment that allowed for "a whole range of things in between," said one former administration official familiar with the opinion. On Dec. 28, 2001, the Justice Department Office of Legal Counsel weighed in with another opinion, arguing that U.S. courts had no jurisdiction to review the treatment of foreign prisoners at Guantanamo Bay. The appeal of Gitmo from the start was that, in the view of administration lawyers, the base existed in a legal twilight zone - or "the legal equivalent of outer space," as one former administration lawyer described it. And on Jan. 9, 2002, John Yoo of Justice's Office of Legal Counsel coauthored a sweeping 42-page memo concluding that neither the Geneva Conventions nor any of the laws of war applied to the conflict in Afghanistan.

Cut out of the process, as usual, was Colin Powell's State Department. So were military lawyers for the uniformed services. When State Department lawyers first saw the Yoo memo, "we were horrified," said one. As State saw it, the Justice position would place the United States outside the orbit of international treaties it had championed for years. Two days after the Yoo memo circulated, the State Department's chief legal adviser, William Howard Taft IV, fired a memo to Yoo calling his analysis "seriously flawed." State's most immediate concern was the unilateral conclusion that all captured Taliban were not covered by the Geneva Conventions. "In previous conflicts, the United States has dealt with tens of thousands of detainees without repudiating its obligations under the Conventions," Taft wrote. "I have no doubt we can do so here, where a relative handful of persons is involved."

The White House was undeterred. By Jan. 25, 2002, according to a memo obtained by NEWSWEEK, it was clear that Bush had already decided that the Geneva Conventions did not apply at all, either to the Taliban or Al Qaeda. In the memo, which was written to Bush by Gonzales, the White House legal counsel told the president that Powell had "requested that you reconsider that decision." Gonzales then laid out startlingly broad arguments that anticipated any objections to the conduct of U.S. soldiers or CIA interrogators in the future. "As you have said, the war against terrorism is a new kind of war," Gonzales wrote to Bush. "The nature of the new war places a - high premium on other factors, such as the ability to quickly obtain information from captured terrorists and their sponsors in order to avoid further atrocities against American civilians." Gonzales concluded in stark terms: "In my judgment, this new paradigm renders obsolete Geneva's strict limitations on questioning of enemy prisoners and renders quaint some of its provisions."

Gonzales also argued that dropping Geneva would allow the president to "preserve his flexibility" in the war on terror. His reasoning? That U.S. officials might otherwise be subject to war-crimes prosecutions under the Geneva Conventions. Gonzales said he feared "prosecutors and independent counsels who may in the future decide to pursue unwarranted charges" based on a 1996 U.S. law that bars "war crimes," which were defined to include "any grave breach" of the Geneva Conventions. As to arguments that U.S. soldiers might suffer abuses themselves if Washington did not observe the conventions, Gonzales argued wishfully to Bush that "your policy of providing humane treatment to enemy detainees gives us the credibility to insist on like treatment for our soldiers."

When Powell read the Gonzales memo, he "hit the roof," says a State source. Desperately seeking to change Bush's mind, Powell fired off his own blistering response the next day, Jan. 26, and sought an immediate meeting with the president. The proposed anti-Geneva Convention declaration, he warned, "will reverse over a century of U.S. policy and practice" and have "a high cost in terms of negative international reaction." Powell won a partial victory: On Feb. 7, 2002, the White House announced that the United States would indeed apply the Geneva Conventions to the Afghan war - but that Taliban and Qaeda detainees would still not be afforded prisoner-of-war status. The White House's halfway retreat was, in the eyes of State Department lawyers, a "hollow" victory for Powell that did not fundamentally change the administration's position. It also set the stage for the new interrogation procedures ungoverned by international law.

What Bush seemed to have in mind was applying his broad doctrine of pre-emption to interrogations: to get information that could help stop terrorist acts before they could be carried out. This was justified by what is known in counter terror circles as the "ticking time bomb" theory - the idea that when faced with an imminent threat by a terrorist, almost any method is justified, even torture.

With the legal groundwork laid, Bush began to act. First, he signed a secret order granting new powers to the CIA. According to knowledgeable sources, the president's directive authorized the CIA to set up a series of secret detention facilities outside the United States, and to question those held in them with unprecedented harshness. Washington then negotiated novel "status of forces agreements" with foreign governments for the secret sites. These agreements gave immunity not merely to U.S. government personnel but also to private contractors. (Asked about the directive last week, a senior administration official said, "We cannot comment on purported intelligence activities.")

The administration also began "rendering" - or delivering terror suspects to foreign governments for interrogation. Why? At a classified briefing for senators not long after 9/11, CIA Director George Tenet was asked whether Washington was going to get governments known for their brutality to turn over Qaeda suspects to the United States. Congressional sources told NEWSWEEK that Tenet suggested it might be better sometimes for such suspects to remain in the hands of foreign authorities, who might be able to use more aggressive interrogation methods. By 2004, the United States was running a covert charter airline moving CIA prisoners from one secret facility to another, sources say. The reason? It was judged impolitic (and too traceable) to use the U.S. Air Force.

At first - in the autumn of 2001 - the Pentagon was less inclined than the CIA to jump into the business of handling terror suspects. Rumsfeld himself was initially opposed to having detainees sent into DOD custody at Guantanamo, according to a DOD source intimately involved in the Gitmo issue. "I don't want to be jailer to the goddammed world," said Rumsfeld. But he was finally persuaded. Those sent to Gitmo would be hard-core Qaeda or other terrorists who might be liable for war-crimes prosecutions, and who would likely, if freed, "go back and hit us again," as the source put it.

In mid-January 2002 the first plane-load of prisoners landed at Gitmo's Camp X-Ray. Still, not everyone was getting the message that this was a new kind of war. The first commander of the MPs at Gitmo was a one-star from the Rhode Island National Guard, Brig. Gen. Rick Baccus, who, a Defense source recalled, mainly "wanted to keep the prisoners happy." Baccus began giving copies of the Qur'an to detainees, and he organized a special meal schedule for Ramadan. "He was even handing out printed 'rights cards'," the Defense source recalled. The upshot was that the prisoners were soon telling the interrogators, "Go f - - - yourself, I know my rights." Baccus was relieved in October 2002, and Rumsfeld gave military intelligence control of all aspects of the Gitmo camp, including the MPs.

Pentagon officials now insist that they flatly ruled out using some of the harsher interrogation techniques authorized for the CIA. That included one practice - reported last week by The New York Times - whereby a suspect is pushed underwater and made to think he will be drowned. While the CIA could do pretty much what it liked in its own secret centers, the Pentagon was bound by the Uniform Code of Military Justice. Military officers were routinely trained to observe the Geneva Conventions. According to one source, both military and civilian officials at the Pentagon ultimately determined that such CIA techniques were "not something we believed the military should be involved in."

But in practical terms those distinctions began to matter less. The Pentagon's resistance to rougher techniques eroded month by month. In part this was because CIA interrogators were increasingly in the same room as their military-intelligence counterparts. But there was also a deliberate effort by top Pentagon officials to loosen the rules binding the military.

Toward the end of 2002, orders came down the political chain at DOD that the Geneva Conventions were to be reinterpreted to allow tougher methods of interrogation. "There was almost a revolt" by the service judge advocates general, or JAGs, the top military lawyers who had originally allied with Powell against the new rules, says a knowledgeable source. The JAGs, including the lawyers in the office of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Gen. Richard Myers, fought their civilian bosses for months - but finally lost. In April 2003, new and tougher interrogation techniques were approved. Covertly, though, the JAGs made a final effort. They went to see Scott Horton, a specialist in international human-rights law and a major player in the New York City Bar Association's human-rights work. The JAGs told Horton they could only talk obliquely about practices that were classified. But they said the U.S. military's 50-year history of observing the demands of the Geneva Conventions was now being overturned. "There is a calculated effort to create an atmosphere of legal ambiguity" about how the conventions should be interpreted and applied, they told Horton. And the prime movers in this effort, they told him, were DOD Under Secretary for Policy Douglas Feith and DOD general counsel William Haynes. There was, they warned, "a real risk of a disaster" for U.S. interests.

The approach at Gitmo soon reflected these changes. Under the leadership of an aggressive, self-assured major general named Geoffrey Miller, a new set of interrogation rules became doctrine. Ultimately what was developed at Gitmo was a "72-point matrix for stress and duress," which laid out types of coercion and the escalating levels at which they could be applied. These included the use of harsh heat or cold; - withholding food; hooding for days at a time; naked isolation in cold, dark cells for more than 30 days, and threatening (but not biting) by dogs. It also permitted limited use of "stress positions" designed to subject detainees to rising levels of pain.

While the interrogators at Gitmo were refining their techniques, by the summer of 2003 the "postwar" insurgency in Iraq was raging. And Rumsfeld was getting impatient about the poor quality of the intelligence coming out of there. He wanted to know: Where was Saddam? Where were the WMD? Most immediately: Why weren't U.S. troops catching or forestalling the gangs planting improvised explosive devices by the roads? Rumsfeld pointed out that Gitmo was producing good intel. So he directed Steve Cambone, his under secretary for intelligence, to send Gitmo commandant Miller to Iraq to improve what they were doing out there. Cambone in turn dispatched his deputy, Lt. Gen. William (Jerry) Boykin - later to gain notoriety for his harsh comments about Islam - down to Gitmo to talk with Miller and organize the trip. In Baghdad in September 2003, Miller delivered a blunt message to Brig. Gen. Janis Karpinski, who was then in charge of the 800th Military Police Brigade running Iraqi detentions. According to Karpinski, Miller told her that the prison would thenceforth be dedicated to gathering intel. (Miller says he simply recommended that detention and intelligence commands be integrated.) On Nov. 19, Abu Ghraib was formally handed over to tactical control of military-intelligence units.

By the time Gitmo's techniques were exported to Abu Ghraib, the CIA was already fully involved. On a daily basis at Abu Ghraib, says Paul Wayne Bergrin, a lawyer for MP defendant Sgt. Javal Davis, the CIA and other intel officials "would interrogate, interview prisoners exhaustively, use the approved measures of food and sleep deprivation, solitary confinement with no light coming into cell 24 hours a day. Consequently, they set a poor example for young soldiers but it went even further than that."

Today there is no telling where the scandal will bottom out. But it is growing harder for top Pentagon officials, including Rumsfeld himself, to absolve themselves of all responsibility. Evidence is growing that the Pentagon has not been forthright on exactly when it was first warned of the alleged abuses at Abu Ghraib. U.S. officials continued to say they didn't know until mid-January. But Red Cross officials had alerted the U.S. military command in Baghdad at the start of November. The Red Cross warned explicitly of MPs' conducting "acts of humiliation such as [detainees'] being made to stand naked... with women's underwear over the head, while being laughed at by guards, including female guards, and sometimes photographed in this position." Karpinski recounts that the military-intel officials there regarded this criticism as funny. She says: "The MI officers said, 'We warned the [commanding officer] about giving those detainees the Victoria's Secret catalog, but he wouldn't listen'." The Coalition commander in Iraq, Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez, and his Iraq command didn't begin an investigation until two months later, when it was clear the pictures were about to leak.

Now more charges are coming. Intelligence officials have confirmed that the CIA inspector general is conducting an investigation into the death of at least one person at Abu Ghraib who had been subject to questioning by CIA interrogators. The Justice Department is likely to open full-scale criminal investigations into this CIA-related death and two other CIA interrogation-related fatalities.

As his other reasons for war have fallen away, President Bush has justified his ouster of Saddam Hussein by saying he's a "torturer and murderer." Now the American forces arrayed against the terrorists are being tarred with the same epithet. That's unfair: what Saddam did at Abu Ghraib during his regime was more horrible, and on a much vaster scale, than anything seen in those images on Capitol Hill. But if America is going to live up to its promise to bring justice and democracy to Iraq, it needs to get to the bottom of what happened at Abu Ghraib.

Powell scolds aide after interview interrupted

By The Associated Press (as published on MSNBC).

Secretary of State Colin Powell chastised a press aide for trying to cut short the taping of a television interview Sunday.Powell, speaking from a Dead Sea resort in Jordan, was listening to a final question from moderator Tim Russert, who was in the Washington studio of NBC’s “Meet the Press.”

In the broadcast, aired several hours after the interview was conducted, Powell abruptly disappears from view. Briefly seen are swaying palm trees and the water, backdrops for the interview.

Powell can be heard saying to the aide, “He’s still asking a question.” The secretary then told Russert, “Tim, I’m sorry I lost you.”

NBC identified the aide as Emily Miller, a deputy press secretary.

Russert responded: “I don’t know who did that. I think that was one of your staff, Mr. Secretary.” The host added: “I don’t think that’s appropriate.”

With the cameras still on the water, Powell snapped, “Emily get out of the way.” He then instructed the crew to “bring the camera back,” and told Russert to go ahead with the last question.

After Powell answered, Russert thanked the secretary for his “willingness to overrule his press aide’s attempt to abruptly cut off our discussion.”

Here is the full text of the article in case the link goes bad:

http://msnbc.msn.com/id/4992866/

Powell scolds aide after interview interrupted

‘I don’t think that’s appropriate,’ host Tim Russert says

The Associated Press

Updated: 3:29 p.m. ET May 16, 2004

WASHINGTON - Secretary of State Colin Powell chastised a press aide for trying to cut short the taping of a television interview Sunday.

Powell, speaking from a Dead Sea resort in Jordan, was listening to a final question from moderator Tim Russert, who was in the Washington studio of NBC’s “Meet the Press.”

In the broadcast, aired several hours after the interview was conducted, Powell abruptly disappears from view. Briefly seen are swaying palm trees and the water, backdrops for the interview.

Powell can be heard saying to the aide, “He’s still asking a question.” The secretary then told Russert, “Tim, I’m sorry I lost you.”

NBC identified the aide as Emily Miller, a deputy press secretary.

Russert responded: “I don’t know who did that. I think that was one of your staff, Mr. Secretary.” The host added: “I don’t think that’s appropriate.”

With the cameras still on the water, Powell snapped, “Emily get out of the way.” He then instructed the crew to “bring the camera back,” and told Russert to go ahead with the last question.

After Powell answered, Russert thanked the secretary for his “willingness to overrule his press aide’s attempt to abruptly cut off our discussion.”

Five interviews scheduled

State Department spokeswoman Julie Reside said Powell had scheduled five interviews, one after another, and that NBC went over the agreed upon time limit. She said every effort was made to get NBC to finish up, but that other networks had booked satellite time for interviews with Powell.

The executive producer of “Meet the Press,” Betsy Fischer, said Powell was 45 minutes late for the interview and that “everyone’s satellite schedules already had to be rescheduled” anyway.

She said the exchange was not edited out because most taped interviews are not altered before airing.

Fischer said Miller called right after the taping to “express her displeasure” that the interview ran long. Fischer also said Powell called Russert a few hours later to apologize.

The State Department would not confirm either call or that Miller was the aide addressed by Powell.

This is from the May 16, 2004 program of

Meet the Press.

This is pretty unbelievable. Colin Powell's press aide attempted to put an early end to the interview by suddenly moving the camera away from Powell (right after Powell addresses the torture situation and right before Russert asks a hard-hitting question about the fake nigerian yellow cake WMD evidence he cited within his U.N. speech). Powell gets her out of the way somehow, manages to get the camera pointed in the right direction, and resumes the interview. You can hear him say "Emily, get out of the way."

Here's the clip that contains what I mention above (happens about half way through):

Colin Powell Clip - Meet The Press (12 MB)

It happens about half way through, right after Powell's admission that he and numerous top officials, including Condi Rice and Rummy, were made aware of the torture situation via a report from the Red Cross they all received way back in mid-February 2004.

Update 4:49 pm: Use one of the three mirrors below:

Here's the first mirror (of the interview parts one and two):

http://synthesize.us/~leif/weblog/mirror/05-16-04-colin.html

Thanks Leif!

Here's a complete mirror (of all three clips):

Colin Powell On Meet The Press - Part 1 of 2

Colin Powell On Meet The Press - Part 2 of 2

Colin Powell On Meet The Press - Apology for Bogus WMD Evidence and Press Aide Interruption Highlights

Thanks Dave!

Here's a second mirror (of all three clips):

Colin Powell On Meet The Press - Part 1 of 2

Colin Powell On Meet The Press - Part 2 of 2

Colin Powell On Meet The Press - Apology for Bogus WMD Evidence and Press Aide Interruption Highlights

Thanks Reid!

Third mirror of all three clips:

Colin Powell On Meet The Press - Part 1 of 2

Colin Powell On Meet The Press - Part 2 of 2

Colin Powell On Meet The Press - Apology for Bogus WMD Evidence and Press Aide Interruption Highlights

Thanks Steve!

Here's a Fourth mirror (woo hoo!):

All three clips are located here.

Thanks Richard!

The Gray Zone

How a secret Pentagon program came to Abu Ghraib

By Sy Hersh for the New Yorker.

The roots of the Abu Ghraib prison scandal lie not in the criminal inclinations of a few Army reservists but in a decision, approved last year by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, to expand a highly secret operation, which had been focussed on the hunt for Al Qaeda, to the interrogation of prisoners in Iraq. Rumsfeld's decision embittered the American intelligence community, damaged the effectiveness of élite combat units, and hurt America's prospects in the war on terror.According to interviews with several past and present American intelligence officials, the Pentagon's operation, known inside the intelligence community by several code words, including Copper Green, encouraged physical coercion and sexual humiliation of Iraqi prisoners in an effort to generate more intelligence about the growing insurgency in Iraq. A senior C.I.A. official, in confirming the details of this account last week, said that the operation stemmed from Rumsfeld's long-standing desire to wrest control of America's clandestine and paramilitary operations from the C.I.A...

Rumsfeld reacted in his usual direct fashion: he authorized the establishment of a highly secret program that was given blanket advance approval to kill or capture and, if possible, interrogate "high value" targets in the Bush Administration's war on terror. A special-access program, or sap-subject to the Defense Department's most stringent level of security-was set up, with an office in a secure area of the Pentagon. The program would recruit operatives and acquire the necessary equipment, including aircraft, and would keep its activities under wraps. America's most successful intelligence operations during the Cold War had been saps, including the Navy's submarine penetration of underwater cables used by the Soviet high command and construction of the Air Force's stealth bomber. All the so-called "black" programs had one element in common: the Secretary of Defense, or his deputy, had to conclude that the normal military classification restraints did not provide enough security...

In 2003, Rumsfeld's apparent disregard for the requirements of the Geneva Conventions while carrying out the war on terror had led a group of senior military legal officers from the Judge Advocate General's (jag) Corps to pay two surprise visits within five months to Scott Horton, who was then chairman of the New York City Bar Association's Committee on International Human Rights. "They wanted us to challenge the Bush Administration about its standards for detentions and interrogation," Horton told me. "They were urging us to get involved and speak in a very loud voice. It came pretty much out of the blue. The message was that conditions are ripe for abuse, and it's going to occur." The military officials were most alarmed about the growing use of civilian contractors in the interrogation process, Horton recalled. "They said there was an atmosphere of legal ambiguity being created as a result of a policy decision at the highest levels in the Pentagon. The jag officers were being cut out of the policy formulation process." They told him that, with the war on terror, a fifty-year history of exemplary application of the Geneva Conventions had come to an end.

Here is the full text of the entire article at:

http://www.newyorker.com/fact/content/?040524fa_fact

The Gray Zone

By Seymour M. Hersh

The New Yorker

Saturday 15 May 2004

How a secret Pentagon program came to Abu Ghraib.

The roots of the Abu Ghraib prison scandal lie not in the criminal inclinations of a few Army reservists but in a decision, approved last year by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, to expand a highly secret operation, which had been focussed on the hunt for Al Qaeda, to the interrogation of prisoners in Iraq. Rumsfeld's decision embittered the American intelligence community, damaged the effectiveness of élite combat units, and hurt America's prospects in the war on terror.

According to interviews with several past and present American intelligence officials, the Pentagon's operation, known inside the intelligence community by several code words, including Copper Green, encouraged physical coercion and sexual humiliation of Iraqi prisoners in an effort to generate more intelligence about the growing insurgency in Iraq. A senior C.I.A. official, in confirming the details of this account last week, said that the operation stemmed from Rumsfeld's long-standing desire to wrest control of America's clandestine and paramilitary operations from the C.I.A.

Rumsfeld, during appearances last week before Congress to testify about Abu Ghraib, was precluded by law from explicitly mentioning highly secret matters in an unclassified session. But he conveyed the message that he was telling the public all that he knew about the story. He said, "Any suggestion that there is not a full, deep awareness of what has happened, and the damage it has done, I think, would be a misunderstanding." The senior C.I.A. official, asked about Rumsfeld's testimony and that of Stephen Cambone, his Under-Secretary for Intelligence, said, "Some people think you can bullshit anyone."

The Abu Ghraib story began, in a sense, just weeks after the September 11, 2001, attacks, with the American bombing of Afghanistan. Almost from the start, the Administration's search for Al Qaeda members in the war zone, and its worldwide search for terrorists, came up against major command-and-control problems. For example, combat forces that had Al Qaeda targets in sight had to obtain legal clearance before firing on them. On October 7th, the night the bombing began, an unmanned Predator aircraft tracked an automobile convoy that, American intelligence believed, contained Mullah Muhammad Omar, the Taliban leader. A lawyer on duty at the United States Central Command headquarters, in Tampa, Florida, refused to authorize a strike. By the time an attack was approved, the target was out of reach. Rumsfeld was apoplectic over what he saw as a self-defeating hesitation to attack that was due to political correctness. One officer described him to me that fall as "kicking a lot of glass and breaking doors." In November, the Washington Post reported that, as many as ten times since early October, Air Force pilots believed they'd had senior Al Qaeda and Taliban members in their sights but had been unable to act in time because of legalistic hurdles. There were similar problems throughout the world, as American Special Forces units seeking to move quickly against suspected terrorist cells were compelled to get prior approval from local American ambassadors and brief their superiors in the chain of command.

Rumsfeld reacted in his usual direct fashion: he authorized the establishment of a highly secret program that was given blanket advance approval to kill or capture and, if possible, interrogate "high value" targets in the Bush Administration's war on terror. A special-access program, or sap-subject to the Defense Department's most stringent level of security-was set up, with an office in a secure area of the Pentagon. The program would recruit operatives and acquire the necessary equipment, including aircraft, and would keep its activities under wraps. America's most successful intelligence operations during the Cold War had been saps, including the Navy's submarine penetration of underwater cables used by the Soviet high command and construction of the Air Force's stealth bomber. All the so-called "black" programs had one element in common: the Secretary of Defense, or his deputy, had to conclude that the normal military classification restraints did not provide enough security.

"Rumsfeld's goal was to get a capability in place to take on a high-value target-a standup group to hit quickly," a former high-level intelligence official told me. "He got all the agencies together-the C.I.A. and the N.S.A.-to get pre-approval in place. Just say the code word and go." The operation had across-the-board approval from Rumsfeld and from Condoleezza Rice, the national-security adviser. President Bush was informed of the existence of the program, the former intelligence official said.

The people assigned to the program worked by the book, the former intelligence official told me. They created code words, and recruited, after careful screening, highly trained commandos and operatives from America's élite forces-Navy seals, the Army's Delta Force, and the C.I.A.'s paramilitary experts. They also asked some basic questions: "Do the people working the problem have to use aliases? Yes. Do we need dead drops for the mail? Yes. No traceability and no budget. And some special-access programs are never fully briefed to Congress."

In theory, the operation enabled the Bush Administration to respond immediately to time-sensitive intelligence: commandos crossed borders without visas and could interrogate terrorism suspects deemed too important for transfer to the military's facilities at Guantánamo, Cuba. They carried out instant interrogations-using force if necessary-at secret C.I.A. detention centers scattered around the world. The intelligence would be relayed to the sap command center in the Pentagon in real time, and sifted for those pieces of information critical to the "white," or overt, world.

Fewer than two hundred operatives and officials, including Rumsfeld and General Richard Myers, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, were "completely read into the program," the former intelligence official said. The goal was to keep the operation protected. "We're not going to read more people than necessary into our heart of darkness," he said. "The rules are 'Grab whom you must. Do what you want.'"

One Pentagon official who was deeply involved in the program was Stephen Cambone, who was named Under-Secretary of Defense for Intelligence in March, 2003. The office was new; it was created as part of Rumsfeld's reorganization of the Pentagon. Cambone was unpopular among military and civilian intelligence bureaucrats in the Pentagon, essentially because he had little experience in running intelligence programs, though in 1998 he had served as staff director for a committee, headed by Rumsfeld, that warned of an emerging ballistic-missile threat to the United States. He was known instead for his closeness to Rumsfeld. "Remember Henry II-'Who will rid me of this meddlesome priest?'" the senior C.I.A. official said to me, with a laugh, last week. "Whatever Rumsfeld whimsically says, Cambone will do ten times that much."

Cambone was a strong advocate for war against Iraq. He shared Rumsfeld's disdain for the analysis and assessments proffered by the C.I.A., viewing them as too cautious, and chafed, as did Rumsfeld, at the C.I.A.'s inability, before the Iraq war, to state conclusively that Saddam Hussein harbored weapons of mass destruction. Cambone's military assistant, Army Lieutenant General William G. (Jerry) Boykin, was also controversial. Last fall, he generated unwanted headlines after it was reported that, in a speech at an Oregon church, he equated the Muslim world with Satan.

Early in his tenure, Cambone provoked a bureaucratic battle within the Pentagon by insisting that he be given control of all special-access programs that were relevant to the war on terror. Those programs, which had been viewed by many in the Pentagon as sacrosanct, were monitored by Kenneth deGraffenreid, who had experience in counter-intelligence programs. Cambone got control, and deGraffenreid subsequently left the Pentagon. Asked for comment on this story, a Pentagon spokesman said, "I will not discuss any covert programs; however, Dr. Cambone did not assume his position as the Under-Secretary of Defense for Intelligence until March 7, 2003, and had no involvement in the decision-making process regarding interrogation procedures in Iraq or anywhere else."

In mid-2003, the special-access program was regarded in the Pentagon as one of the success stories of the war on terror. "It was an active program," the former intelligence official told me. "It's been the most important capability we have for dealing with an imminent threat. If we discover where Osama bin Laden is, we can get him. And we can remove an existing threat with a real capability to hit the United States-and do so without visibility." Some of its methods were troubling and could not bear close scrutiny, however.

By then, the war in Iraq had begun. The sap was involved in some assignments in Iraq, the former official said. C.I.A. and other American Special Forces operatives secretly teamed up to hunt for Saddam Hussein and-without success-for Iraqi weapons of mass destruction. But they weren't able to stop the evolving insurgency.

In the first months after the fall of Baghdad, Rumsfeld and his aides still had a limited view of the insurgency, seeing it as little more than the work of Baathist "dead-enders," criminal gangs, and foreign terrorists who were Al Qaeda followers. The Administration measured its success in the war by how many of those on its list of the fifty-five most wanted members of the old regime-reproduced on playing cards-had been captured. Then, in August, 2003, terror bombings in Baghdad hit the Jordanian Embassy, killing nineteen people, and the United Nations headquarters, killing twenty-three people, including Sergio Vieira de Mello, the head of the U.N. mission. On August 25th, less than a week after the U.N. bombing, Rumsfeld acknowledged, in a talk before the Veterans of Foreign Wars, that "the dead-enders are still with us." He went on, "There are some today who are surprised that there are still pockets of resistance in Iraq, and they suggest that this represents some sort of failure on the part of the Coalition. But this is not the case." Rumsfeld compared the insurgents with those true believers who "fought on during and after the defeat of the Nazi regime in Germany." A few weeks later-and five months after the fall of Baghdad-the Defense Secretary declared,"It is, in my view, better to be dealing with terrorists in Iraq than in the United States."

Inside the Pentagon, there was a growing realization that the war was going badly. The increasingly beleaguered and baffled Army leadership was telling reporters that the insurgents consisted of five thousand Baathists loyal to Saddam Hussein. "When you understand that they're organized in a cellular structure," General John Abizaid, the head of the Central Command, declared, "that . . . they have access to a lot of money and a lot of ammunition, you'll understand how dangerous they are."

The American military and intelligence communities were having little success in penetrating the insurgency. One internal report prepared for the U.S. military, made available to me, concluded that the insurgents'"strategic and operational intelligence has proven to be quite good." According to the study:

"Their ability to attack convoys, other vulnerable targets and particular individuals has been the result of painstaking surveillance and reconnaissance. Inside information has been passed on to insurgent cells about convoy/troop movements and daily habits of Iraqis working with coalition from within the Iraqi security services, primarily the Iraqi Police force which is rife with sympathy for the insurgents, Iraqi ministries and from within pro-insurgent individuals working with the CPA's so-called Green Zone."

The study concluded, "Politically, the U.S. has failed to date. Insurgencies can be fixed or ameliorated by dealing with what caused them in the first place. The disaster that is the reconstruction of Iraq has been the key cause of the insurgency. There is no legitimate government, and it behooves the Coalition Provisional Authority to absorb the sad but unvarnished fact that most Iraqis do not see the Governing Council"-the Iraqi body appointed by the C.P.A.-"as the legitimate authority. Indeed, they know that the true power is the CPA."

By the fall, a military analyst told me, the extent of the Pentagon's political and military misjudgments was clear. Donald Rumsfeld's "dead-enders" now included not only Baathists but many marginal figures as well-thugs and criminals who were among the tens of thousands of prisoners freed the previous fall by Saddam as part of a prewar general amnesty. Their desperation was not driving the insurgency; it simply made them easy recruits for those who were. The analyst said, "We'd killed and captured guys who had been given two or three hundred dollars to 'pray and spray'"-that is, shoot randomly and hope for the best. "They weren't really insurgents but down-and-outers who were paid by wealthy individuals sympathetic to the insurgency." In many cases, the paymasters were Sunnis who had been members of the Baath Party. The analyst said that the insurgents "spent three or four months figuring out how we operated and developing their own countermeasures. If that meant putting up a hapless guy to go and attack a convoy and see how the American troops responded, they'd do it." Then, the analyst said, "the clever ones began to get in on the action."

By contrast, according to the military report, the American and Coalition forces knew little about the insurgency: "Human intelligence is poor or lacking . . . due to the dearth of competence and expertise. . . . The intelligence effort is not coördinated since either too many groups are involved in gathering intelligence or the final product does not get to the troops in the field in a timely manner." The success of the war was at risk; something had to be done to change the dynamic.

The solution, endorsed by Rumsfeld and carried out by Stephen Cambone, was to get tough with those Iraqis in the Army prison system who were suspected of being insurgents. A key player was Major General Geoffrey Miller, the commander of the detention and interrogation center at Guantánamo, who had been summoned to Baghdad in late August to review prison interrogation procedures. The internal Army report on the abuse charges, written by Major General Antonio Taguba in February, revealed that Miller urged that the commanders in Baghdad change policy and place military intelligence in charge of the prison. The report quoted Miller as recommending that "detention operations must act as an enabler for interrogation."

Miller's concept, as it emerged in recent Senate hearings, was to "Gitmoize" the prison system in Iraq-to make it more focussed on interrogation. He also briefed military commanders in Iraq on the interrogation methods used in Cuba-methods that could, with special approval, include sleep deprivation, exposure to extremes of cold and heat, and placing prisoners in "stress positions" for agonizing lengths of time. (The Bush Administration had unilaterally declared Al Qaeda and other captured members of international terrorist networks to be illegal combatants, and not eligible for the protection of the Geneva Conventions.)

Rumsfeld and Cambone went a step further, however: they expanded the scope of the sap, bringing its unconventional methods to Abu Ghraib. The commandos were to operate in Iraq as they had in Afghanistan. The male prisoners could be treated roughly, and exposed to sexual humiliation.

"They weren't getting anything substantive from the detainees in Iraq," the former intelligence official told me. "No names. Nothing that they could hang their hat on. Cambone says, I've got to crack this thing and I'm tired of working through the normal chain of command. I've got this apparatus set up-the black special-access program-and I'm going in hot. So he pulls the switch, and the electricity begins flowing last summer. And it's working. We're getting a picture of the insurgency in Iraq and the intelligence is flowing into the white world. We're getting good stuff. But we've got more targets"-prisoners in Iraqi jails-"than people who can handle them."

Cambone then made another crucial decision, the former intelligence official told me: not only would he bring the sap's rules into the prisons; he would bring some of the Army military-intelligence officers working inside the Iraqi prisons under the sap'sauspices. "So here are fundamentally good soldiers-military-intelligence guys-being told that no rules apply," the former official, who has extensive knowledge of the special-access programs, added. "And, as far as they're concerned, this is a covert operation, and it's to be kept within Defense Department channels."

The military-police prison guards, the former official said, included "recycled hillbillies from Cumberland, Maryland." He was referring to members of the 372nd Military Police Company. Seven members of the company are now facing charges for their role in the abuse at Abu Ghraib. "How are these guys from Cumberland going to know anything? The Army Reserve doesn't know what it's doing."

Who was in charge of Abu Ghraib-whether military police or military intelligence-was no longer the only question that mattered. Hard-core special operatives, some of them with aliases, were working in the prison. The military police assigned to guard the prisoners wore uniforms, but many others-military intelligence officers, contract interpreters, C.I.A. officers, and the men from the special-access program-wore civilian clothes. It was not clear who was who, even to Brigadier General Janis Karpinski, then the commander of the 800th Military Police Brigade, and the officer ostensibly in charge. "I thought most of the civilians there were interpreters, but there were some civilians that I didn't know," Karpinski told me. "I called them the disappearing ghosts. I'd seen them once in a while at Abu Ghraib and then I'd see them months later. They were nice-they'd always call out to me and say, 'Hey, remember me? How are you doing?'" The mysterious civilians, she said, were "always bringing in somebody for interrogation or waiting to collect somebody going out." Karpinski added that she had no idea who was operating in her prison system. (General Taguba found that Karpinski's leadership failures contributed to the abuses.)

By fall, according to the former intelligence official, the senior leadership of the C.I.A. had had enough. "They said, 'No way. We signed up for the core program in Afghanistan-pre-approved for operations against high-value terrorist targets-and now you want to use it for cabdrivers, brothers-in-law, and people pulled off the streets'"-the sort of prisoners who populate the Iraqi jails. "The C.I.A.'s legal people objected," and the agency ended its sap involvement in Abu Ghraib, the former official said.

The C.I.A.'s complaints were echoed throughout the intelligence community. There was fear that the situation at Abu Ghraib would lead to the exposure of the secret sap, and thereby bring an end to what had been, before Iraq, a valuable cover operation. "This was stupidity," a government consultant told me. "You're taking a program that was operating in the chaos of Afghanistan against Al Qaeda, a stateless terror group, and bringing it into a structured, traditional war zone. Sooner or later, the commandos would bump into the legal and moral procedures of a conventional war with an Army of a hundred and thirty-five thousand soldiers."

The former senior intelligence official blamed hubris for the Abu Ghraib disaster. "There's nothing more exhilarating for a pissant Pentagon civilian than dealing with an important national security issue without dealing with military planners, who are always worried about risk," he told me. "What could be more boring than needing the coöperation of logistical planners?" The only difficulty, the former official added, is that, "as soon as you enlarge the secret program beyond the oversight capability of experienced people, you lose control. We've never had a case where a special-access program went sour-and this goes back to the Cold War."

In a separate interview, a Pentagon consultant, who spent much of his career directly involved with special-access programs, spread the blame. "The White House subcontracted this to the Pentagon, and the Pentagon subcontracted it to Cambone," he said. "This is Cambone's deal, but Rumsfeld and Myers approved the program." When it came to the interrogation operation at Abu Ghraib, he said, Rumsfeld left the details to Cambone. Rumsfeld may not be personally culpable, the consultant added, "but he's responsible for the checks and balances. The issue is that, since 9/11, we've changed the rules on how we deal with terrorism, and created conditions where the ends justify the means."

Last week, statements made by one of the seven accused M.P.s, Specialist Jeremy Sivits, who is expected to plead guilty, were released. In them, he claimed that senior commanders in his unit would have stopped the abuse had they witnessed it. One of the questions that will be explored at any trial, however, is why a group of Army Reserve military policemen, most of them from small towns, tormented their prisoners as they did, in a manner that was especially humiliating for Iraqi men.

The notion that Arabs are particularly vulnerable to sexual humiliation became a talking point among pro-war Washington conservatives in the months before the March, 2003, invasion of Iraq. One book that was frequently cited was "The Arab Mind," a study of Arab culture and psychology, first published in 1973, by Raphael Patai, a cultural anthropologist who taught at, among other universities, Columbia and Princeton, and who died in 1996. The book includes a twenty-five-page chapter on Arabs and sex, depicting sex as a taboo vested with shame and repression. "The segregation of the sexes, the veiling of the women . . . and all the other minute rules that govern and restrict contact between men and women, have the effect of making sex a prime mental preoccupation in the Arab world," Patai wrote. Homosexual activity, "or any indication of homosexual leanings, as with all other expressions of sexuality, is never given any publicity. These are private affairs and remain in private." The Patai book, an academic told me, was "the bible of the neocons on Arab behavior." In their discussions, he said, two themes emerged-"one, that Arabs only understand force and, two, that the biggest weakness of Arabs is shame and humiliation."

The government consultant said that there may have been a serious goal, in the beginning, behind the sexual humiliation and the posed photographs. It was thought that some prisoners would do anything-including spying on their associates-to avoid dissemination of the shameful photos to family and friends. The government consultant said, "I was told that the purpose of the photographs was to create an army of informants, people you could insert back in the population." The idea was that they would be motivated by fear of exposure, and gather information about pending insurgency action, the consultant said. If so, it wasn't effective; the insurgency continued to grow.

"This shit has been brewing for months," the Pentagon consultant who has dealt with saps told me. "You don't keep prisoners naked in their cell and then let them get bitten by dogs. This is sick." The consultant explained that he and his colleagues, all of whom had served for years on active duty in the military, had been appalled by the misuse of Army guard dogs inside Abu Ghraib. "We don't raise kids to do things like that. When you go after Mullah Omar, that's one thing. But when you give the authority to kids who don't know the rules, that's another."

In 2003, Rumsfeld's apparent disregard for the requirements of the Geneva Conventions while carrying out the war on terror had led a group of senior military legal officers from the Judge Advocate General's (jag) Corps to pay two surprise visits within five months to Scott Horton, who was then chairman of the New York City Bar Association's Committee on International Human Rights. "They wanted us to challenge the Bush Administration about its standards for detentions and interrogation," Horton told me. "They were urging us to get involved and speak in a very loud voice. It came pretty much out of the blue. The message was that conditions are ripe for abuse, and it's going to occur." The military officials were most alarmed about the growing use of civilian contractors in the interrogation process, Horton recalled. "They said there was an atmosphere of legal ambiguity being created as a result of a policy decision at the highest levels in the Pentagon. The jag officers were being cut out of the policy formulation process." They told him that, with the war on terror, a fifty-year history of exemplary application of the Geneva Conventions had come to an end.

The abuses at Abu Ghraib were exposed on January 13th, when Joseph Darby, a young military policeman assigned to Abu Ghraib, reported the wrongdoing to the Army's Criminal Investigations Division. He also turned over a CD full of photographs. Within three days, a report made its way to Donald Rumsfeld, who informed President Bush.

The inquiry presented a dilemma for the Pentagon. The C.I.D. had to be allowed to continue, the former intelligence official said. "You can't cover it up. You have to prosecute these guys for being off the reservation. But how do you prosecute them when they were covered by the special-access program? So you hope that maybe it'll go away." The Pentagon's attitude last January, he said, was "Somebody got caught with some photos. What's the big deal? Take care of it." Rumsfeld's explanation to the White House, the official added, was reassuring: "'We've got a glitch in the program. We'll prosecute it.' The cover story was that some kids got out of control."