Daily Kos dude Markos Moulitsas Zuniga cruised through the Colbert Report last week. (April 6, 2006, I think)

Video-Markos Moulitsas Zuniga on the Colbert Report (12 MB)

Audio-Markos Moulitsas Zuniga on the Colbert Report (MP3 - 8 MB)

He's got new book out called

Crashing the Gate

This is from the April 25, 2004 program of

Meet the Press.

Bob Woodward and Prince Bandar On Meet The Press.

Each interview is available in two parts. (About 35 MB each)

This ties in with the Bob Woodward On 60 Minutes footage from a few weeks ago.

Check out Bob Woodward's new book,

Plan of Attack.

This is from the May 2, 2004 program of

Meet the Press.

This directory contains the entire interview in one big file and three smaller files:

Joseph Wilson On Meet The Press.

Check out Joseph Wilson's new book:

The Politics of Truth: Inside the Lies that Led to War and Betrayed My Wife's CIA Identity: A Diplomat's Memoir.

One thing Joseph said that sticks out in my mind is that daddy Shrub said whoever leaked the information about Wilson's wife was an "insidious traitor."

Does anyone know where he said this or when? Update: Oh okay. He said it in 1999. But it still applies -- to Karl Rove and the Cheney gang in this case:

"I have nothing but contempt and anger for those who betray the trust by exposing the names of our [intelligence] sources. They are, in my view, the most insidious of traitors."

This is from the April 18, 2004 program of 60 Minutes.

This piece details, among other things, the Shrub's secret allocation of 700 million dollars to Tommy Franks for his "secret" war plans that were in place in early 2002.

Here's the whole thing in two big 25 MB ish chunks.

Smaller files and highlights on the way...

Check out Bob Woodward's new book,

Plan of Attack.

This is from the March 21, 2004 program of 60 Minutes.

Richard Clarke, former top advisor on Counterterrorism for the Shrub, Clinton Terrorism Czar, and an appointed expert for both Daddy Shrub and Reagan, has written a book Against All Enemies that exposes a number of different things going on over at the old White House during the days after 911.

I've made the files available in one and four parts.

911 Before and After

(Richard Clarke on 60 Minutes - March 21, 2004)

Walter Isaacson is a former chairman and CEO of CNN, the President of the Aspen Institute, and the author of A Benjamin Franklin Reader.

Franklin worshippers such as myself will get a lot of mileage out of this interview. There are some lovely descriptions of my man Ben hanging out and doing cool things up until the day he died.

It made me want to read the book.

This is from the October 22, 2003 program.

Interview with Walter Isaacson (Small - 15 MB)

The Daily Show (The best news on television.)

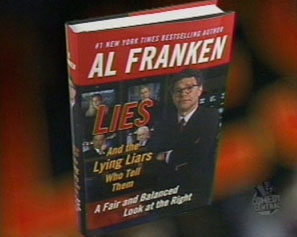

This book is awesome! I'm only about half way through it right now. It does a great job of nailing the right on their incessant distortion of the truth -- and backs it all up with footnoted facts!

You should just but it now!

Anyway, this was emailed to me sometime ago. Not sure where it came from, but I know it's been circulated pretty heavily through numerous channels at this point. I know that Salon has it in it's quagmire of a website somewhere, but they won't even let you read the front page anymore without suffering through an lengthy ad, so I didn't have time to try to find the link.

"Lies and the Lying Liars Who Tell Them"

An excerpt from Al Franken's new book.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

By Al Franken

Aug. 27, 2003 | God chose me to write this book.

God began our conversation by clearing something up. Some of George W. Bush's friends say that Bush believes God called him to be president during these times of trial. But God told me that He/She/It had actually chosen Al Gore by making sure that Gore won the popular vote and, God thought, the Electoral College. "THAT WORKED FOR EVERYONE ELSE," God said."What about Tilden?" I asked, referring to the 1876 debacle.

"QUIET!" God snapped. God was angry.

God said that after 9/11, George W. Bush squandered a unique moment of national unity. That instead of rallying the country around a program of mutual purpose and sacrifice, Bush cynically used the tragedy to solidify his political power and pursue an agenda that panders to his base and serves the interests of his corporate backers.

God told me that Bush squandered a $4.6 trillion surplus and is plunging us into deficits as far as God can see. And that Bush squandered another surplus. The surplus of goodwill from the rest of the world that he had inherited from Bill Clinton.

And this was pissing God off.

"Lies and the Lying Liars Who Tell Them"

An excerpt from Al Franken's new book.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

By Al Franken

Aug. 27, 2003 | God chose me to write this book.

Just the fact that you are reading this is proof not just of God's existence, but also of His/Her/Its beneficence. That's right. I am not certain of God's precise gender. But I am certain that He/She/It chose me to write this book.

This isn't hubris. I'm not saying this in an egotistical way. God didn't choose me because I'm the greatest writer who ever lived. That was William Shakespeare, whose work I have a passing familiarity with. No. I just happened to be the right vessel at the right time. If something in this book makes you laugh, it was God's joke. If something makes you think, it's because God had a good point to make.

The reason I know God chose me is because God spoke to me personally.

God began our conversation by clearing something up. Some of George W. Bush's friends say that Bush believes God called him to be president during these times of trial. But God told me that He/She/It had actually chosen Al Gore by making sure that Gore won the popular vote and, God thought, the Electoral College. "THAT WORKED FOR EVERYONE ELSE," God said.

"What about Tilden?" I asked, referring to the 1876 debacle.

"QUIET!" God snapped. God was angry.

God said that after 9/11, George W. Bush squandered a unique moment of national unity. That instead of rallying the country around a program of mutual purpose and sacrifice, Bush cynically used the tragedy to solidify his political power and pursue an agenda that panders to his base and serves the interests of his corporate backers.

God told me that Bush squandered a $4.6 trillion surplus and is plunging us into deficits as far as God can see. And that Bush squandered another surplus. The surplus of goodwill from the rest of the world that he had inherited from Bill Clinton.

And this was pissing God off.

He/She/It was right. But it sounded like a lot of work.

"Look, God, I'm flattered, but I think you got the wrong guy. The kind of book you're talking about would require months of research."

And God said, "LET THERE BE GOOGLE. AND LET THERE BE LEXISNEXIS."

"Very funny, God. I use Google all the time."

"YES, I KNOW," God said. "FOR HOT ASIAN TEENS."

"You must be thinking of my son, Joe."

"AL? I'M OMNISCIENT."

"Okay, okay." I changed the subject. "It's just that I can't do this book myself."

"LEAVE THAT TO ME," God boomed.

And that's when Harvard called.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Harvard's Kennedy School of Government asked me to serve as a fellow at its Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics, and Public Policy. After my varied and celebrated career in television, movies, publishing, and the lucrative world of corporate speaking, being a fellow at Harvard seemed, frankly, like a step down.

I couldn't think of anything less appealing than molding the minds of tomorrow's leaders, unless it was spending fireside evenings sipping sherry with great minds at the Faculty Club. Yawn.

To my surprise and delight, though, all Harvard wanted me to do was show up every once in a while and write something about something. That gave me an idea.

"Would it be okay if I wrote a scathingly partisan attack on the right-wing media and the Bush administration?"

"No problem," Harvard said absentmindedly.

"Count me in," I replied. "From now on call me 'Professor Franken.'"

"No," Harvard said, "you're not a professor. But you can run a study group on the topic of your choosing."

"Great," I said. "I've got the perfect topic: Write My Son's Harvard College Application Essay."

"No," they said. "Harvard students already know how to write successful Harvard applications, Al. We want you to teach them something new."

Harvard was right where I wanted it. "How about if the topic is: How to Research My Book?"

"Sure," Harvard said. "Most of our professors teach that course. Why, in the Biochemistry department, most of the graduate-level courses are--"

Harvard was boring me. "I gotta run, Harvard. Thanks."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

I had my Nexis, I had my Google, I had my Harvard fellowship, and I had my fourteen research assistants. I sat down to write. Nothing.

So I got on my knees and prayed for guidance. "How, God, can I best do Your work through this book? Who, dear Lord, is the audience for a book like this? And what's a good title?"

God answered, "YOU KNOW THOSE SHITTY BOOKS BY ANN COULTER AND BERNIE GOLDBERG?"

"The bestsellers that claim there's a liberal bias in the media?" I asked.

"TOTAL BULLSHIT," God said. "START BY ATTACKING THEM. HE'S CLEARLY A DISGRUNTLED FORMER EMPLOYEE, AND SHE JUST LIES. BY THE WAY, THERE'S SOMETHING SERIOUSLY WRONG WITH HER."

"That's pretty obvious."

"SO GO AFTER THEM, THE WHOLE LIBERAL BIAS MYTH, AND THEN GO AFTER THE RIGHT-WING MEDIA. ESPECIALLY FOX."

"Okay, God, I'm writing this down."

"THEN USE THEM AS A JUMPING-OFF POINT TO GO AFTER BUSH. YOU KNOW, BIG TAX CUTS FOR THE RICH, SURGING UNEMPLOYMENT, IGNORING EVERYONE BUT HIS CORPORATE BUDDIES, SCREWING THE ENVIRONMENT, PISSING OFF THE REST OF THE WORLD. THAT STUFF. AND THAT'S YOUR BOOK."

"Got it. One last thing. Title."

"HOW ABOUT BEARERS OF FALSE WITNESS AND THE FALSE WITNESS THAT THEY BEAR?"

"Hmm. I, uh, I'll work with that."

So I've been immediately sidetracked by the announcement of Amazon's Search Inside The Book Feature. I'd reprint the announcement, but it's a stupid image file so you'll have to go look for yourself. It does look neat though.

| It's out -- finally! If you've read his novel, then you know that Cory Doctorow really knows how to tell a story. His new short story collection is finally available for purchase, and I promise it won't let you down. |

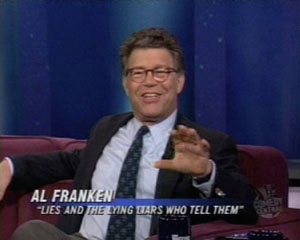

The Prince of Fair and Balanced was on the

The Daily Show last night.

Al took the liberty of pointing out the hypocrisy of the Shrub wearing a flight suit and performing in his little aircraft carrier escapade when, in reality, he not only let his daddy pull strings for him to get into the National Guard so he wouldn't have to go to Vietnam, but then, he didn't even show up for duty, and went AWOL for a year!

I might have to break this up into highlights. But here's the whole thing for now.

Be sure to buy Al's Book too. I'm just starting it, and I already love it. Everybody I've talked to couldn't put the thing down till they were done.

Enjoy!

Al Franken On The Daily Show - Complete (Small - 13 MB)

Al Franken On The Daily Show - Part 1 of 2 (Small - 8 MB)

Al Franken On The Daily Show - Part 2 of 2 (Small - 6 MB)

The Daily Show (The best news on television.)

Note: This is a short story, not a book, but I'm putting it in here anyway. It's the sequel to the book. And if you haven't read the book yet, you can read it for free, and then read the short story.

Cory Doctorow has written a lovely short story sequel to Down and Out In the Magic Kingdom.

Salon published it a few weeks ago. In case you need to print it out to read it (like I do), I've provided a complete version of the text.

God. God. The person was so old, saurian and slow, nearly 300, an original revolutionary from the dawn of the Bitchun Society. Just a kid, then, rushing the barricades, destroying the churches, putting on a homemade police uniform and forming the first ad-hoc police force. Boldly walking out of a shop with an armload of groceries, not paying a cent, shouting jauntily over his shoulder to "Charge it up to the ol' Whuffie, all right?"What a time! Society in hybrid, halfway Bitchun. The religious ones eschewing backup, dying without any hope of recovery, entrusting their souls to Heaven instead of a force-grown clone that would accept an upload of their backup when the time came. People actually dying, dying in such number that there were whole industries built around them: gravediggers and funeral directors in quiet suits! People refusing free energy, limitless food, immortality.

And the Bitchun Society outwaited them. They died one at a time, and the revolutionaries were glad to see them go, each one was one less dissenter, until all that remained was the reputation economy, the almighty Whuffie Point, and a surfeit of everything except space.

Adrian's grin was rictus, the hard mirth of the revolutionaries when the last resister was planted in the ground, their corpses embalmed rather than recycled. Years and decades and centuries ticked past, lessons learned, forgotten, relearned. Lovers, strange worlds, inventions and symphonies and magnificent works of art, and ahead, oh ahead, the centuries unrolling, an eternity of rebirth and relearning, the consciousness living on forever.

And then it was over, and Adrian was sweating and still grinning, the triumphant hurrah of the revolutionary echoing in his mind, the world his oyster.

Truncat

By Cory Doctorow

"Adrian, you have a million friends," his mother said. "That's an audited stat. I'm sorry if you feel isolated, but none of us are moving to Bangalore just so you can chum it up with this fellow."

Adrian fought to control his irritation. His mother was always cranky before breakfast, and a full-blown fight could extend that mood through the whole day. No one needed that. "Mom," he said, twisting his body in the narrow, three-person coffin he shared with his folks so that he could look her in the eye, "I'm not asking you to move to India. All I'm doing is explaining my paper."

His mother snorted. "_The Last Generation on Earth_, really! Adrian, if I were your instructor, I sure wouldn't graduate you on the strength of something like that. I don't really care if that boy in India has convinced the ITT people that his trendy little thesis holds water. The University of Toronto has higher standards than that."

It had been a mistake to even discuss it with his mother. At 180, she was hardly equipped to understand the pressures he and his miniscule generation faced. He should've just written it and stuck it in his advisor's public directory. Only just that he'd had the coolest idea in the night and he'd reflexively bounced it off of her: once his generation reached maturity, the whole planet would be post-human, and a new, new era would start. The Bitchun Society, Phase II.

"OK, Mom, OK. I'm going to get breakfast -- you want to come?"

"No," she said, rolling back over. "I'm going to wait for your father."

Past her, he saw the snoring bulk of his father, still zonked out even through their heated exchange. Adrian grasped the ceiling rails and inched himself out of the coffin and into the public corridor.

His gut was rumbling, but the queue for the canteen was still lengthy, packed with breakfasters from the warren where he made his home. Reluctantly, he decided to skip breakfast and go to his private spot. It was almost backup time, and he needed to do some purging.

Truth be told, Adrian's private spot was not all that private, and it was a humungous bitch to reach. His netpals liked to compare notes on their hidey-holes, and Adrian was certain that he had the shittiest, least practical of the lot.

First, Adrian got on the subway, opting to go deadhead for a faster load-time. He stepped into the sparkling cryochamber at the Downsview station, conjured a HUD against his field of vision, and granted permission to be frozen. The next thing he knew, he was thawing out on the Union station platform, pressed belly-to-butt with a couple thousand other commuters who'd opted for the same treatment. In India, where this kind of convenience-freezing was even more prevalent, Mohan had observed that the reason their generation was small for their age was that they spent so much of it in cold-sleep, conserving space in transit. Adrian might've been 18, but he figured that he'd spent at least one cumulative year frozen.

Adrian shuffled through the crowd and up the stairs to the steady-temp surface, peeling off the routing sticker that the cryo had stuck to his shoulder. His tummy was still rumbling, so he popped the sticker in his mouth and chewed until it had dissolved, savoring the steaky flavor and the burst of calories. The guy who'd figured out edible routing tags had Whuffie to spare: Adrian's mom knew someone who knew someone who knew him, and she said that he had an entire subaquatic palace to rattle around in.

A clamor of swallowing noises filled his ears, as the crowd subvocalized, carrying on conversations with distant friends. Adrian basked in the warm, simulated sunlight emanating from the dome overhead. He was going outside of the dome in a matter of minutes, and he had a sneaking suspicion that he was going to be plenty cold soon enough. He patted his little rucksack and made sure he had his cowl with him.

He inched his way through the crowd down Bay Street to the ferrydocks, absently paging through his public directory, looking at the stuff he'd accumulated in the night. It would all have to go, of course, but he wanted a chance to run some of it before then. Most of it was crap, of course. The average backup of the average citizen of the Bitchun Society was hardly interesting enough to warrant flash-baking, but there were gems, oh yes.

His private spot hung tantalizingly before him, just outside of the dome. The press of bodies parted and he lengthened his step to the docks, boarded the ferry with a nod to the operator in his booth, and hustled into one of the few seats on the prow, pulling on his cowl as the ferry pushed away and headed off toward the airlock at Toronto Island.

It was even colder than the last time. The telltale on his cowl showed -48 degrees C with the wind-chill. His nose and toes went instantly numb, and he tucked them under the cowl's warmth.

His private place was just a short slosh from the westernmost beach at Hanlon's Point on Toronto Island, a forgotten smartbuoy, bristling with self-repairing electronics, like a fractal porcupine. It had been a couple weeks since his last foray there, and in the interim, the buoy had grown more instrumentation, closing over the narrow entryway into its console-pod. Cursing under his breath, Adrian wrapped his cowl around his hands and broke off the antennae, tossing them into the choppy Lake Ontario froth. Then he climbed inside and held his breath.

Breakers crashing on Hanlon's Point. Distant hum of the airlock. A plane buzzing overhead. Silence, of a sort. A half-eaten sandwich mouldered near his right ham. Disgustedly, he pitched it out, silently cursing the maintenance crews that periodically made their way out to his buoy and tried to puzzle out the inexplicable damage he'd wrought on it.

But the silence, ah. His mother never understood the need for silence. She was comforted by the farting, breathing, shuffling swarm of humanity that bracketed her at all times. She'd spent a couple decades jaunting, tin-plated and iron-lunged in the vast emptiness of space, and she'd had her fill of quiet and then some. Adrian, though, with 18 (or 17) years of the teeming hordes of the post-want Bitchun Society, couldn't get enough of it.

His public directory was bursting with backups, the latest batch that his contemporaries around the world had passed to him. Highly illegal, the backups were out-of-date consciousness-memoirs created by various citizens of the Bitchun Society, a weekly hedge against irreparable physical harm.

Theoretically, when you made a new backup, the old one was discarded, the file copied to a nonexistent node on the distributed network formed by the combined processing power of the implanted computers carried by every member of the Bitchun Society. Theoretically.

Adrian paged through the directory. Carrying one of the bootlegs into a backup terminal would mean instant detection. Even xmitting it to someone else was risky, and prone to being sniffed. But Mohan, his netpal in Bangalore, had authored a sweet little tool that allowed for xmission over the handshaking and routing channel, a narrowband circuit that carried unreliable -- and hence untraceable -- information that would have been overheard in the main data-channels. The Million had quickly adopted the tool, and they used it to pass their contraband to each other, copying the bootlegs prior to erasing them when their own weekly backup sched rolled around.

Adrian had good Whuffie with the Million. Nothing like Mohan, of course, but still good -- he reliably stored bootlegs for the Million, even if it meant putting off his own backup until he could find safe storage for all those materials entrusted to him. He didn't mind: being a high-Whuffie storage repository meant that he got everyone's most precious bootlegs for safekeeping.

Like this one, the backup of a third-gen Bitchun, born at the end of the XXIst Century, female (though that hadn't lasted long). Seventy years later, her/his backup was a rich tapestry of memories, spectacular space battles, incredible sexual adventures, side-splitting jokes, exotic flavors and esoteric knowledge absorbed from brilliant teachers all over the planet. He'd held onto it for two weeks now, and flash-baked it nearly every day.

Time to do it again. Quickly, he executed the command, and shuddered as that consciousness was rolled up into a bullet of memories and insights and fired directly into his mind, unfolding overtop of his own thoughts and dreams so that for a moment, he _was_ that person, her/his self enveloping Adrian with an infinitude of bombarding sense impressions.

It ebbed away, the rush fading in a synaptic crackle, leaving him trembling and wrung-out. He slumped against the buoy's spiny interior and brought up a HUD and started an agent searching for another member of the Million with storage to spare for a copy of it.

#

Backup days were flash-baking days. In the buoy, Adrian flash-baked a dozen times, alternating between timeworn favorites and the tastiest morsels deposited by the rest of the Million. He gorged himself on the antique consciousnesses of the immortals of the Bitchun Society, past satiety and full to bursting, his head throbbing dangerously.

Each time, he carefully passed the file to the network, waiting while the churning, clunking handshaking channel completed the transfer. He didn't mind the wait: it gave him a moment for the synesthetic rushes to pass. Time grew short, and his gut growled protests, sending up keotic belches that filled the closed space with the smell of esters.

One more, one more, deposited for safekeeping by Mohan himself in the night. Mohan sat at the river's headwaters, the source of all the bootlegs. He was the theoretically nonexistent node to which the backup network flushed its expired files. When he identified a keeper, it had to be good. Adrian had saved it for last, and now he rolled it and jammed it into his brain.

God. God. The person was so _old_, saurian and slow, nearly 300, an original revolutionary from the dawn of the Bitchun Society. Just a kid, then, rushing the barricades, destroying the churches, putting on a homemade police uniform and forming the first ad-hoc police force. Boldly walking out of a shop with an armload of groceries, not paying a cent, shouting jauntily over his shoulder to "Charge it up to the ol' Whuffie, all right?"

What a time! Society in hybrid, halfway Bitchun. The religious ones eschewing backup, dying without any hope of recovery, entrusting their souls to Heaven instead of a force-grown clone that would accept an upload of their backup when the time came. People actually _dying_, dying in such number that there were whole industries built around them: gravediggers and funeral directors in quiet suits! People refusing free energy, limitless food, immortality.

And the Bitchun Society outwaited them. They died one at a time, and the revolutionaries were glad to see them go, each one was one less dissenter, until all that remained was the reputation economy, the almighty Whuffie Point, and a surfeit of everything except space.

Adrian's grin was rictus, the hard mirth of the revolutionaries when the last resister was planted in the ground, their corpses embalmed rather than recycled. Years and decades and centuries ticked past, lessons learned, forgotten, relearned. Lovers, strange worlds, inventions and symphonies and magnificent works of art, and ahead, oh ahead, the centuries unrolling, an eternity of rebirth and relearning, the consciousness living on forever.

And then it was over, and Adrian was sweating and still grinning, the triumphant hurrah of the revolutionary echoing in his mind, the world his oyster.

"Oh, Mohan," he breathed to himself. "Oh, that was terrific." He scouted the network on his HUD, looking for a reliable member of the Million, someone he could offload this to so that he could get it back after his own backup was done. There -- a girl in France, directory wide open. He started the transfer, then settled back to bask in the remembered exultation of his last flash-bake.

His cochlea chimed. The HUD said it was his mother. Damn.

"Hi, Mom," he said.

"Adrian!" she said. "Where are you?" She wasn't in a good mood, that much was clear.

"Uh," he said. "On the subway," he extemporized. "I'm gonna see if Mr. Bosco can see me." Bosco was the admissions advisor at the University of Toronto that he'd been sucking up to lately, trying to charm the old ad-hocrat into letting him into school for the fall semester. It wasn't easy: the undergrad program at the University was winding down in favor of exclusive, high-Whuffie one-on-one grad programs. Teaching the sparse undergrads of the Million was anything but a glamor gig.

"Bosco?" his mother said, mollified. "Well, that's. . .good. Listen, I don't want you talking about this admissions paper idea of yours -- nobody wants to hear about how you and your friends are the last generation of humans. Every generation thinks they're special -- it's just not so."

"Fine," he said. He wouldn't talk to Bosco anytime soon if he could help it, anyway.

"Your father worked with you on that good N-P Complete proof. Present that instead."

"Sure," he said. The revolutionary still echoed in his mind, like distant gunfire.

His mother talked on, and he kept his answers down to one syllable until she let him go. Back in the quiet of the buoy, he quickly purged all the bootlegs from his public directory, pulled his cowl tight and reluctantly climbed outside and back to the Island, there to await the ferry.

#

Adrian's backup was uneventful, a moment before a secure broadband terminal while his life flashed before his eyes, extracted and spread out to a redundant assortment of nodes on the fifteen billion person network that carpeted the earth.

This obeisance to the Bitchun Society completed, he took to the downtown streets, waiting for the files he'd farmed out and deleted to trickle back in. Waiting for the revolutionary's backup, for another taste of exultation and grandiose triumph. He walked all the way from Union Station to Bloor, a good hour in the glottal press of the lunchtime crowd, and still the revolutionary failed to reappear. Clucking his tongue in annoyance, he ducked into a doorway and checked for the French girl.

Her directory was purged! In the space of mere hours, she'd discarded all the third-party files deposited in her personal directory!

It was really inexcusable. The only possible mitigation would be if she'd passed the file on to someone else before deleting it. He spawned an agent and set it hunting for the file through the network of the Million, branching out in binary search from the nodes that were most commonly employed by the French girl.

His mother rang his cochlea again, and he passed her to voicemail, but the ringing stung him into worry. He had a week before the admissions committee deadline at the U of T, and he'd never hear the end of it if he didn't get in. He thought back to the revolutionary, to his participation in the grad-student takeover of the Soc Department in the mid-XXIst, the replacement of tenure with Whuffie.

Those were the days! Real battles, real principles, and the blissful, blessed elbow-room. That's what he needed. Or, failing that, another crack at flash-baking the bootleg. Damn that French bimbo, anyway.

His cochlea rang again, his mother. Resigned, he answered.

"Adrian, where are you?" She sounded like she was in a better mood, anyway.

"I'm at Yonge and Bloor, Mom. Having a walk, looking for somewhere to get some lunch."

"What did Mr. Bosco say?"

Damn, damn, damn. "He said he'd think about it -- he'll get back to me with comments tomorrow."

"Really?" his mother said, sounding genuinely interested. Bosco had never really given him the time of day.

"Yeah," he said. "I think he liked it, the N-P Complete thing, I mean. I didn't mention the other thing."

"Funny," she said, and her voice was all ice now. "He didn't mention your visit at all when I spoke to him just now."

The blood drained from Adrian's face. He wouldn't hear the end of this for some time. "Uh," he said.

"Just listen to me, kid, don't say anything else. You're in enough trouble as it is. I've got your father conferenced in, and I can tell you he isn't looking like he's very happy.

"Now, here's how it's going to be. I've set up an appointment with Bosco in one hour. I had to call in a lot of favors to do it, and you will be on time. Your father will be there, and you'll tell Bosco how excited you are by this opportunity. You won't mention this stupidity you've been chasing. You will show him how diligent you are in your studies, show him how much you can benefit the University, and you will be cheerful and smart. Do you understand?"

"Yes," Adrian said. Jesus, she was furious.

"One hour," she said, and rang off.

#

Adrian's agent found the bootleg again just as he reached the waiting room at Innis College. The French one _had_ passed it on before deleting it, to another girl in Kansas. Sighing with relief, he queued the download just as his father arrived.

Adrian's father was apparent 22, hardly older-seeming than Adrian himself, though his real age was closer to 122. All Adrian's life, his father had kept himself at an apparent age that was just a few years older than Adrian's own, following a bit of child-rearing wisdom that had been trendy fifty years before, just as the Bitchun Society started to mete out Whuffie-punishments for those people selfish enough to contribute to the overcrowding by reproducing. The logic ran that having a father of playmate-size would reduce the loneliness of the children of the diminished generation of the day.

At 22, Adrian's father was heavyset and acne-pocked, his meaty pelt bulging whenever it came into contact with the light cotton djellaba he wore around town.

He gave Adrian a curt nod when he arrived, his eyes fixed on a space in the middle-distance where his omnipresent HUD shone for him alone. He took a seat next to Adrian and rang his cochlea.

Adrian rolled his eyes and answered subvocally. Why his father couldn't have an unmediated conversation was beyond him. "Hi, Dad," he said.

"Hi there. Had a good morning?"

"Good enough," Adrian answered. "How's Mom?"

His father subvocalized a chuckle, the sound in Adrian's cochlea blending weirdly with the swallowing sounds from his father's throat. "She's pretty angry. Don't worry about it -- we'll do a dog-n-pony for Bosco and she'll forget all about it."

Bosco opened the office-door and greeted them. Adrian's father answered audibly, his voice rusty from disuse.

In Bosco's leatherbound academic cave of an office, the two adults chattered boringly and lengthily. Adrian knew the drill, knew that it could be a long time before anyone could have anything to say to him.

Sneaking a glance at his father and Bosco, he rolled up the revolutionary's backup and flash-baked it.

The life unrolled over his mind, the early days of the Bitchun Society, the physical battles and the ego-clashes; first adulthood lived as a nomad, trekking around the globe; a second and third adulthood, a fourth, moving towards that moment at which the backup was taken, when eternity unrolled, and

_snip_

it cut off.

Adrian's eyes popped open. _Damn_. Truncat! The file had been chopped short during transmission between the nodes. Half the revolutionary's life, vanished into a random scattering of bits and aether.

Bosco was looking expectantly at him, heavy-lidded, wavy hair and thick eyebrows and crinkles at the corners of his eyes from long hours of thinking. He had said something. Hurriedly, Adrian zipped through his short-term AV capture on a HUD, played back to Bosco saying, "Well, Adrian, this is a very well-prepared entrance paper. Can you tell me what it is about mathematics that interests you?"

Now Bosco and Adrian's father were both staring, and Adrian mimed concentration, as though he were genuinely considering his answer. In truth, he was paging through his files for the canned response his mother had provided him with, but there was no sense in admitting it.

"I've always loved math," he recited, struggling to remember the phrasing. "I just can't help seeing the mathematical relationships in everyday life. It just makes sense to me."

Bosco nodded, the ritual response satisfying him. Adrian's father gave him an appraising look and went back to wrangling with Bosco. It all came down to Whuffie, anyway -- did Adrian's parents have enough reputation capital that their gratitude to Bosco outweighed the upset the teaching staff would feel when they were saddled with a lowly undergrad?

#

The meeting was hardly over before his mother was conferencing Adrian and his father in. As it turned out, Adrian's father had been dumping a realtime video-stream to her all through the meeting, she'd seen it all. "Adrian," she said, sharply, "What's the matter with you? You were completely out of it during that whole thing."

"I was just thinking, Mom. I got distracted. I think it went well, anyway, right, Dad?"

"Sure, sure," his father subvocalized, patting him on the shoulder. "I think you're all set for next term."

But Adrian's mother was not to be mollified. "Adrian, I'm sick of all this flakiness. I know exactly what you were _thinking_ about --" Adrian's heart sank: how could she know about the bootleg? "All that adolescent hand-wringing about your generation is distracting you from your real priorities, and it's time you smartened up. Grant me private access, I want a look at what you've been up to."

Oh, shit. Hurriedly, Adrian flushed the bootlegs. His mother hadn't gone picking though his files in years, so it took him a moment to remember the mnemonic that erased the bootlegs and all records of their existence from his personal storage. In his cochlea, his mother made impatient noises, and that sure didn't help.

Once the data was flushed, he granted her access. He watched dismally as his system log scrolled by, every file in his storage piping through his mother's keyword filter.

"'The parents of the Million are understandably resentful of their offspring,'" she read, in a dangerous voice. It was the paper he and Mohan had been collaborating on, and he knew she wasn't going to like it. "'For whatever reason, they chose to bring a generation into being at a time when the world wanted nothing but. The sacrifices they've endured since are immense, Whuffie penalties that mount daily as their peers make their disapproval felt. Our parents are stuck in the closest thing the Bitchun Society has to poverty, and it's our fault.'"

She paused and drew breath. "All right, Mom, all right, that's enough," Adrian said. "I'll get rid of it."

She snorted. "You're damned right, you will. Just adolescent nonsense --"

"I know," Adrian said. "I'm sorry." Mohan had a copy, anyway -- he could recover it later.

"Don't switch off my access, either," she said, to Adrian's dismay. "I'll be checking in regularly from now on -- you've got to concentrate on your studies, not this, this --"

Words failed her.

#

Adrian thought his mother would be mollified when Bosco called her later that day to say that he was to be admitted for the summer term in the Department of Applied Mathematics at the University of Toronto. But she couldn't let go of her suspicion that he was up to no good.

Mohan's theory was that she was worked up over the possibility that she was nearly shut of the stigma of mothering one of the Million, and that she feared that he would do something that would rain down fresh shame on her.

So, the random audits of his files continued, daily at different times. Adrian hardly flash-baked at all in the next week, and he fell into a grimy, hyperreal mood, bereft of access to others' consciousnesses. It wasn't that the Bitchun Society had anything to complain about: food, shelter, entertainment, travel, communications -- all of it freely available. No disease that couldn't be cured with rejuve, or, failing that, refreshing from backup into a clone. But three months remained until his term started, three long months of not being able to swap polemics with Mohan, of not being able to roll up the lovely consciousnesses that he scored through Mohan and jam them into his brain.

After a week of it, he was positively buggy, ready to have himself frozen until classes started. During the scarce hours when he and Mohan were awake and online at the same moment, he was able to work remotely off of Mohan's systems, but the lag through the kludged-up channel made it so painful he could hardly bear it.

His salvation came ten days after the acceptance.

He was en route to his private spot when it happened. Thawing out on the kerb outside of Union Station, chewing thoughtfully at his routing tag, he was approached by a stranger. The woman was apparent 17, and a quick back-check of her public ID verified that she was actually 17, another member of the Million, a needle in the demographic haystack. She snuck up on him while he was ruefully paging through the public directories where he'd put his bootlegs the last time his mother had gone tiptoeing through his consciousness, salvaging what he could from the tatters of his beloved collection. She was wearing a cowl like his, and had odd, vaguely Asian features, round-faced and flat-nosed, but with a fair cast to her skin that was almost paper-white. She tapped his shoulder and spoke aloud, a clear, young voice ringing out in the mumbling white-noise of the subvocalizing crowd.

"Hi there!" she said. A few people turned to stare, their eyes flicking up to HUDs where they examined the pair's Whuffie and designation.

"Hello," Adrian said.

"My name's Tina," she said. Her speech had long, spacey vowels in it, the speech of a jaunter somewhere in the dark nothings of interstellar space, crackling through adventure dramas on the net.

"Adrian," he said, and put his hand out.

She chuckled. "Wow, you really do that, huh?"

"What?"

"Shake hands! I've seen it in historicals, but never in real life." She shook his hand, harder than was necessary. "I'm pleased to meet you, Adrian. What do you do?"

"What?" he said again.

"You know, what's your role? I used to help out with the hydroponics, before we came here. Now my folks say I've got to find something new to do. What do you do?"

"Uh," Adrian said. She was a jaunter, freshly back from space, probably landed at Aristide Interplanetary just north of the city. He didn't know much about jaunters, but he did know that their version of the Bitchun Society was a little nonstandard. "I'm a student," he said.

"Wow!" she said. "Full time? What do you study?"

"I'm doing applied maths at U of T. Will be, anyway," he corrected himself. "This summer."

Her face clouded for a moment as she chewed this over. "How long are you going to be doing that for?"

"It's a four-year degree."

"Four years?" she said, shocked.

"Yes."

"That's a long time! Who's going to take your job when you go?"

"What job?" Adrian asked. He wasn't sure how he'd been drawn into this conversation, but he was enjoying it, in a disorienting way.

"The job you do now," she said, as though explaining something to an idiot.

He fished for words, then watched as comprehension dawned on her. "You don't do anything now, do you?"

He grinned. "Not really, no."

She clapped her hands. "You people are really freaky, you know that? What do you _do_ all day, if you're not working?"

Adrian opened his mouth and she looked at him with such guilelessness that he made a rash and wonderful decision.

"I'll show you," he said, and struck off to the ferry-docks.

#

It was tough squeezing two people into the buoy, but they managed to clamber in, with much blushing and inadvertent placement of hands and elbows. Adrian's sexual experiences to date had been entirely teledildonic, and the reality of his close proximity to someone of the opposite sex had his ears glowing pink.

Tina took it all in stride, remarking that she'd been in much closer quarters aboard the ship she'd grown up on, bending time and space on a long voyage out to what turned out to be a hunk of dead, airless rock. "It's pretty cool for Earth, though," she allowed.

Adrian covered his embarrassment by furiously combing the network for some decent bootlegs. Though not officially one of the Million, Tina was a generational comrade, and entitled to try out flash-baking under the terms of the agreement that Mohan had insisted the Million subscribe to if they wanted access to his booty. Adrian's researches located a real plum, the revolutionary's backup, trunced to a mere nubbin of its former glory, but still a good choice for Tina's first experience. He downloaded it from a boy in Vancouver and pushed it into Tina's public directory. She cast her eyes up and they tracked over her HUD.

"What's this?" she asked.

"It's what I do," Adrian said, and sent her the flash-baking app. "We'll run it together."

Together, they executed the app, rolling the bootleg and baking it. Adrian suppressed a groan of disappointment. The file was so foreshortened that it barely registered for him, just a distant hurrah of triumph and then it was gone.

Tina, though, was taken completely aback, her breathing heavy, her jaw hanging limp. Slowly, her almond eyes fluttered open, and she rolled her head from side to side langorously.

"That was really fine," she said. "Really. How do you know Nestor?"

"Who?"

"The guy in the backup -- Nestor. He was on the ship with us."

Adrian's heart slammed in his chest. "You _know him_?"

"Yeah!" she said. "Of course! I grew up with him."

Adrian reeled. She knew the revolutionary! He could meet him, get another copy of the bootleg --

"Wait, you _don't_ know Nestor?" she said.

He shook his head, his mind racing. He would meet him, go with him to see Mohan, tell him their theories about the Million --

"How did you get this if you don't know Nestor?" she asked.

His thoughts screeched to a halt. "It's a bootleg," he said. "An illicit copy."

She gave him a hard look and he realized what was weird about her eyes, her skin. She'd been tin-plated, iron-lunged and steely-eyed all her life, until she made Earth. She'd only had naked eyes for a few days. Now, they looked steely, distant and considering.

"You're saying that you got this without Nestor's permission?" she asked.

So he explained about the bootlegs, about Mohan's discovery of a backdoor that let him designate his personal storage with the generic ID used for the system's discard bin, how Mohan had distributed the backups over the handshaking channel. He was warming up to a discussion of generational politics when she interrupted him.

"That's awful!" she said. "These are _private_ -- how can you just trade them around?"

He hadn't actually given it any thought in years. "It's not like we're spying on our friends," he said, hastily. "These people are strangers. We'll never know who they are -- but it's the only way we can learn about --"

"Nestor's not a stranger," she said, flatly. "He ran the engine-room on my ship. He won't like this very much, either."

"Wait!" Adrian said, alarmed. "You're not going to _tell_ him, are you? We could get into a lot of trouble."

"You mean _you_ could get into a lot of trouble," she said.

"Fine," he said, hotly. "Go ahead. That's what I get for making friends with a stranger."

That stopped her. "We're friends?" she said.

"Sure," he said. "You're the only person I've ever brought here. That's friendship, isn't it?"

"But you just met me!" she said. "How can you be my friend?" She seemed genuinely distressed.

"Well, I just liked you is all," he said. "You asked me good questions. I thought I could ask you some. I showed you this place, let you flash-bake one of my bootlegs --"

"And that makes us friends?" She shook her head. "On the ship, we treated everyone like that. Friends were really. . ." she dug for the word. "It wasn't so _casual_. Friends were a big deal."

"You see?" Adrian said, glad to be off the subject of the bootlegs. "That's just the kind of thing that makes us great friends -- you don't know your way around Earth and I don't know much about space, so we've got lots to talk about. What were friends like on the ship?"

And off they went, and at first, Adrian was just relieved, but she had wonderful stories, stories of bravery and devotion, of friends scattered to the stars, seas and Earth when the ship returned to Earth, of the hollow longing she felt for them now. Before he knew it, it was nightfall, and he'd located another bootleg, fresh from Mohan, and they flash-baked it and agreed that having the whole file was better than just some little stub of a truncat, but that being said, her friend Nestor had a much more interesting life than the 80 year old painter they'd just run.

When they parted for the night, Adrian took her hand and told her what a wonderful time he'd had with her. "Could you do me a favor, do you think?"

"Sure!" she said, brightly.

"Could you hold onto some files for me?"

If she'd hesitated, even for an instant, he would have taken it back, told her not to bother. He wasn't a _bastard_ -- she was really cool, the first person his age he'd been in company with in years, just wonderful to hang with. She didn't hesitate, not even for an instant.

"Sure," she said, and he moved all the bootlegs he'd picked up that afternoon to her storage.

#

Adrian wasn't really sure what physically proximate friends did for fun, but Tina had all sorts of ideas. They met up for breakfast the next morning at a public maker near Adrian's place, and the queue had never seemed shorter, as they gabbled in the near-silence of the thronged corridor.

They walked while they shovelled post-scarcity waffles and sausage into their mouths, Tina remarking constantly on the crowds, the sheer thronging humanity of it all. The parks were all too dense for fun, but they found ample elbow-room way out in the east end, where untalented sculptors operated public studios in the unpopular former scraplands.

The fight was Adrian's fault. "I want to meet him," Adrian said, as they watched a man with hammer and chisel crawl over a hideous marble lion.

"Him?" Tina said. "Why? He stinks."

Adrian smiled and shushed her. "Not so loud -- anyways, he's not as bad as some of the people around here. No, not him -- Nestor, the ship's engineer. You know --"

Her expression slammed shut. "No. God! No! Adrian, why --" She choked on whatever she was going to say next.

Adrian, taken aback, said carefully, "Why not? I really, you know, _admire_ him."

"But you've been inside his head!" she said, scandalized. "How could you look him in the eye after --" Again, words failed her.

"But that's _why_ I want to meet him! What I saw, what he knows, it just makes so much sense. I feel like he could really tell me what it's all about."

Her eyes took on the aspect of steel again, the million lightyear stare. "If you talk to Nestor, I'll never speak to you again. I'll -- I'll turn you in! I'll report you and all of your pals!"

"Jesus, Tina, what's _wrong_ with you? You're supposed to be my friend and now you're going to _turn me in_?" He was so angry, he could hardly speak. He wished he was talking to her over the network, so that he could just hang up and walk away. He did the next best thing, turning on his heel and walking away.

"Hey," Tina shouted, angry too.

He kept on walking.

#

She found him in his private place, holding a one-sided argument with his mother. "Mom, I'm old enough to get a place of my own, and you can't stop me," he shouted into the buoy's guts. In her cochlea, he heard his mother's grunt of anger, and his HUD was filled with the scrolling system log as she angrily deleted his files, being on a particularly nasty tear that day.

"Mom!" he shouted again. "Talk to me or I'll -- I'll lock you out!"

Tina watched this, half in, half out of the buoy, her bottom exposed to the frigid stinging rain, her face flushed with the captured body-heat in the buoy. Adrian had yet to notice her, too absorbed in his conversation.

"That's it," he said. "I'm locking you out now."

He opened his eyes and sighed back against the buoy's bulkhead. He saw Tina and let out a surprised "Yah!"

He recovered quickly, gave her a nasty look and said, "Get out! Jesus, just leave me alone!"

She'd been calling him, leaving messages on his voicemail for a week, but he had her blocked and the messages just kept getting returned, unheard. Defiantly, she crawled the rest of the way in and huddled as far from him as she could, which still meant that she was halfway in his lap.

"God, they must be stupid in space," Adrian ranted. "Can't you understand I don't want to talk to you? Go away!"

Tina gave him an appraising look. "One thing we learn in space," she said, "is how to out-wait a bad mood. I'm not leaving until we have a chance to talk, and if you don't like it, that's too bad. You're not getting rid of me unless you throw me into the lake."

Adrian fumed and closed his eyes. He searched fruitlessly for a decent bootleg, but his connections had dried up and dropped off in the two weeks since his mother's spotchecks had curtailed his trading. It could take days to build them up again.

"Fine," he said at length. "Say your piece and go, all right?"

"Turn on public access," Tina said. Adrian started to protest, but she fixed him with her stare. "Do it," she said, firmly.

Adrian sighed dramatically and closed his eyes, then watched as all the bootlegs he'd stored with her were passed back to his storage. Everything! "Thanks," he said, cautiously. "What's going on? Are you planting evidence before turning me in?"

She shook her head. "I deserve that, I suppose. There's one more," she said. And a filename appeared in his HUD.

"What is it?" he said.

"Just try it," she said.

He rolled it up and baked it, then grunted in shock. It was Nestor's backup, complete and whole, centuries of life, stretching up to the current day. There was Tina in the memories, her birth on ship, her growing up. There was the voyage, the long trip taken in vain and the long return home. The new memories were mirrorbright and cold as space, all the vigor and passion drained with nothing but a hard waiting in their place.

He opened his eye. "Where --" he began, but couldn't finish. He waved his hands at her.

Tina grinned wryly. "I took it from the ship," she said. "I still have access to its utility files. It's just past Pluto now, spacing out for another mission. That made it a little tricky to transfer, but I got it."

"Thanks," he said.

She tilted her head. "Don't thank me," she said.

It was sinking in now, that hardness, that waiting, the centuries ahead dull and indistinguishable from the ones behind, and no hope of it ever ending. The miserable, fatal knowledge that there was only more of this, more and more, forever, and no break in the monotony. It settled over him like lead weight, sapping everything, even the anger at his mother. Endless days of plenty. . .

"How did he get so, so --"

"We used to say he was 'arid,'" Tina said. "None of the parents on the ship would let the kids go near him, so of course we snuck over to see him whenever we could. He hasn't had a rejuve in, oh, forever, and he looks like a silver skeleton. We'd pester him with questions, and he'd just stare and stare, then finally say something so amazingly depressing."

"But how? He was so, so -- _passionate_. He made me feel like there was a chance, like I could make a difference." Adrian said. That first bootleg, it must have dated back to before the ship left, a relative century before, and it was flushed into Mohan's honey-pot when the ship returned and Nestor made a fresh backup.

Tina shrugged. "Space changes people," she said, simply. "Time, too. He's nearly 400 now, you know. My parents called him a post-person. You know, what comes after people. That's why we didn't ship out again -- they don't want that to happen to them. Nestor wasn't the only one."

Adrian shuddered. A ship full of people like that, years cooped up in quarters tighter than any he'd known on Earth. . .

"You see why I didn't want you to meet him," she said.

"Oh, I can take care of myself," he said. "You didn't have to worry about me."

She gave him another quizzical look. Her glance was more natural now, less spacey. Her skin, too, had taken on a tone that was more human. "I wasn't worried about _you_," she said. "I was worried about Nestor! He's okay most of the time, but when you get him talking about the old days, he just breaks down. You've never seen anyone so miserable. Poor old Nestor," she said, with feeling.

"Say, I've got one more for you, if you're interested," she said. "Brand new," she added.

"Sure," Adrian said and opened his directory. He took the file he found there, rolled it, baked it.

It was Tina, the short life of Tina, the claustrophobia and unimaginable distances of space, the tight and deep friendships in the tiny shipboard community, the loneliness in the crowds of Earth. Her spying him on the streets of this strange and overwhelming city, her relief when he didn't rebuff her. And him -- him, through her eyes, smart and savvy and frightening. Frightening? Yes, his anger and his rejection, his unfathomable values and ideas. It was short, her backup, a mere 17 years' worth of consciousness, and it took him a bare moment to bake it.

Tina was looking down at her feet.

"Hey," Adrian said. "Tina?"

Tina looked up. She was scared, those eyes wide and guileless.

"Yes?" she said.

"Switch on guest access, OK?" Adrian said. Then he pushed her a copy of his last backup.

#

He spent as long as he could bumming around downtown before catching a subway home. His mother hadn't called him since he'd locked her out of his personal storage and sent her a copy of his backup and the flash-baking app, and the thought of seeing her face-to-face made his stomach knot.

Leadenly, he took the stairs down to the subterranean level where his family slept, and hit the door code. It slid open, revealing his father, alone, staring up at the ceiling.

"Dad?" Adrian said. His cochlea rang. He answered.

"Hi, Adrian," his father said, in his ear. He sounded tired.

"Where's Mom?" Adrian asked, with a growing sense of foreboding.

"Oh, she went out," Adrian's father said, vaguely.

"Is she angry?"

Adrian expected a chuckle, but none came. "No," his father said, flatly. "Not angry."

"Are _you_ angry?"

His father shifted his bulk and drew Adrian into a long hug. "No, son, I'm not angry either," he whispered aloud in Adrian's ear.

It took Adrian a moment to register that his father had spoken aloud, and when he did, it hardly eased his nervousness.

"What's going on, Dad?" he asked, finally.

His father sat up, ducking his head for the low ceiling. "I owe you an apology," he said.

"For what?"

His father switched back to subvocal. "All this business with the University. You deserve to choose what you want to do. We had a long talk about it this afternoon, and we decided that it's not our place to tell you what to study. I'll take you to see Bosco in the morning, and we can show him the essay you worked up with your friend in India."

Adrian didn't know what to make of that, except that he felt vaguely guilty. "Why? What changed your mind?"

His father flopped onto his back and stared at the ceiling. "I read the paper," he said. "It's good. Interesting thesis, good execution. Thought-provoking. It's a good paper. You could really start something with it."

"Yeah?" Adrian said, blushing. His HUD flashed an alert. His father was pushing a file into his storage. Adrian examined it: a backup, his father's backup. Adrian understood, now. He knew that if he looked in his father's storage that he'd see a copy of his own backup there.

"Yes. You and your friends, you could have a real destiny. Post-people, the last generation on Earth -- that's smart stuff."

Adrian startled. _Post-person_. He thought of Nestor, saurian, purposeless, cold and hard. Of Tina, looking for a job, a thing to do every day.

A thought occurred to him. "What are you going to do when I start school, Dad?"

"Oh, I don't know. Maybe deadhead for a while, see what things are like in another century. I know that's what your mother wants to do."

They'd talked about deadheading before, but Adrian had never really believed they'd do it. Gone for a century -- frozen in cold sleep like millions of others, waiting to see what the future held.

"I'll miss you," he said.

"Oh, you'll get used to it," Adrian's father said. "I can't tell you how many people I know who're deadheading now. Almost everyone I ever knew, really. We'll see each other again before you know it."

When he woke in the morning, his mother was back, asleep between him and his father. Automatically, he checked his in-box. His mother had sent a copy of her backup, too. He got up quietly, careful not to disturb her, and snuck away.

#

Tina answered on the second ring, sounding groggy.

"'lo?"

"Tina?"

"Hi," she mumbled.

"Listen, do you want a job?" he said.

"Huh?" She was waking up now.

"A job -- do you still want a job?"

"Sure," she said.

"You're hired," he said.

"For what?"

Adrian rolled up and flashed Nestor's backup, feeling the hopeless, helpless weight of eternity. He flashed his mother's backup, his father's. He grinned. "Here, let me dump you the job-requirements," he said, and dumped the files on her.

"Start with these. Send them around, everyone you know. Don't ask for anything in return, but if they send you anything back, pass it around too." He swallowed, prepared a set to send to Mohan. "We're gonna be post-people, but we're gonna do it _right_," he said.

I've been re-reading Down and Out In The Magic Kingdom again, and it really is all that good. If you haven't read it yet, you might want to check out the HTML

version of it online.

Now that it has become apparent that people are ready to look to new ways of managing information, money and intangible assets (such as "knowlege"), it seems like a good time to start talking about what kind of system would be fair and ideal -- just to give us something to strive for as we reshape our future.

Besides being a great read and a lot of fun (which is, of course, always the first requirement of any book I recommend), I feel that this book is an important one, because it really provides lots of excellent tangible examples of how a Reputation Economy might work.

Reputation systems are something that I have been fascinated with and meaning to write about for some time, but there were so many people already writing about them that knew so much more than me, and I realized about this time two years ago that I had so much to learn, I'd better just shut up and learn from other people for a few years before trying to teach anyone else about them.

Basically, in a reputation economy, you are rewarded with points when you do good things for the overall population. These points can vary in value between discounts on merchandise (in certain instances) or simply earning you respect among your peers.

Here's a clip from the Book's Prologue that helps to explain the concept better. (I'm rummaging around for some good papers on this too.)

... Whuffie recaptured the true essence of money: in the old days, if you were broke but respected, you wouldn’t starve; contrariwise, if you were rich and hated, no sum could buy you security and peace. By measuring the thing that money really represented—your personal capital with your friends and neighbors—you more accurately gauged your success.

More on this soon. I just wanted to get the ball rolling...

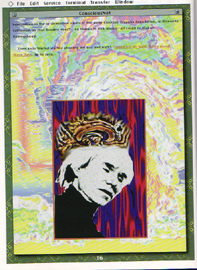

The story I just blogged about the nano tech talks at the cryonics conference reminded me that Timothy Leary wrote about Alcor in the book I worked on with him (Surfing the Conscious Nets). (Contrary to popular belief, however, Tim did not freeze his remains.)

I went and dug up the reference to Alcor, just for fun. For those of you with a copy of Surfing the Conscious Nets around, it's on page 16. For the rest of you, I've created a scan here:

I'm sure this is OK with both Last Gasp publisher Ron Turner, who is a friend of mine, and would consider it promotion for the book, and Tim Leary himself, because he told me in 1995 that it was his dream to have all of his works freely available online. A dying wish, if you will.

(Yeah, we're talking everything. So I'm sure he wouldn't mind a few scans.)

On the bright side of the ledger, John Lilly, Jack Nicholson and Michelle Phillips have escaped with their "souls" intact. So far! Several of the lesser known Gabor sisters, rumor has it, had their pretty heads sliced and diced by Dr. Sidney Cohen's gang. Elvis Presley? Who knows? Walt Disney? Janis Joplin? Jim Morrison? Just who exactly still lives frozen in blessed hibernation in the re-animation vaults of the Alcor-CryoCare Cryonics Foundation, in Riverside, California, as Jimi Hendrix does? -- no thanks to Nick Rogue--all credit to Michael Hollingshead.Then Andy Warhol started phoning me day and night. Cryonics is all Andy thinks about these days. So he says.

A Howard Rheingold Trading Card | I went to see Howard Rheingold speak at some bookstore on the Haight a few nights ago -- I've read excerpts from a friend of mine's copy of Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution, and I can already highly recommend it. |

This is not to say that smart mobs are wise mobs. Not all groups who use new technologies to organize collective action have socially beneficial ends in mind. Criminals, totalitarian governments, spammers, will all be able to take advantage of new capabilities -- just as the first to take advantage of tribes, nation-states, markets, networks included the malevolent as well as the cooperative.

Here is the full text of the interview in case the link goes bad:

http://engaged.well.com/engaged/engaged.cgi?c=inkwell.vue&f=0&t=166&q=0-

[Goto Topics List]

Conference Banner

Howard Rheingold, Smart Mobs

Topic #166, 83 responses, 0 new, Last post on Mon 25 Nov 2002 at 08:09 AM

inkwell.vue 166: Howard Rheingold, Smart Mobs

#0 of 82: Jon Lebkowsky (jonl) Thu 21 Nov 2002 (07:24 AM)

Howard Rheingold was an early Internet adopter who understood quickly how

computing and 'net-based communication could enhance human capabilities. This

fed into an interest in human potential that led Howard to create or

co-create such works as _Higher Creativity_ (1984), _The Cognitive

Connections_ (1986), and _Excursions to the Far Side of the Mind: A Book of

Memes_ (1988). Howard became involved in the WELL in 1985, and this led to

his authorship of _The Virtual Community_, a book about his life online and

the potential for community in cyberspace. Howard was editor of Whole Earth

Review for several years, and of the Millennium Whole Earth Catalog, which

was published in 1994. Howard was the first Executive Editor at HotWired,

but left to build Electric Minds, which was more of an online community/jam

session than a magazine. Howard continues to explore the human impact of new

technologies in _Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution_, which explores the

impact of increasingly ubiquitous wireless communications devices on social

networks, and the evolution of moblike adhocracies that can be either

positive or destructive.

Bruce Umbaugh leads the discussion with Howard. Bruce is a philosopher who

teaches at Webster University's main campus in St. Louis (MO, USA) and via

the Net. His interests include computer ethics, epistemology, philosophy of

science, cognitive science.

Please join me in welcoming Bruce and Howard to inkwell.vue!

inkwell.vue 166: Howard Rheingold, Smart Mobs

#1 of 82: virtual community or butter? (bumbaugh) Thu 21 Nov 2002 (07:44 AM)

Thanks, Jon.

Howard, I've really enjoyed your book. The ideas you're pursuing are as

interesting and engaging as anything I've come across in awhile. So, it's

exciting to have the chance to talk with you here about all this.

I think one of the first things likely to occur to anyone bumping into

*Smart Mobs* is that the title itself is a bit jarring. We usually think of

"mobs" as dumb (and in part for that reason dangerous). We often think of

only individuals as "smart." So a place to start is asking you what smart

mobs are.

inkwell.vue 166: Howard Rheingold, Smart Mobs

#2 of 82: Howard Rheingold (hlr) Thu 21 Nov 2002 (12:01 PM)

The briefest definition is that a smart mob is group of people who use

mobile communications, PCs, and the Internet to organize collective

action. That doesn't mean a whole lot without unpacking it. Maybe it will

help for me to briefly describe the clues that led me to suspect that we

are at the beginning of an important social-technological revolution.

In Tokyo, in early 2000, I couldn't help noticing that so many people were

looking at their telephones rather than listening to them -- and many were

using their thumbs to send text messages to one another. Interesting --

but there are many interesting sights in Tokyo. I recalled this unusual

sight (unusual for American eyes -- elsewhere in the world, around 100

billion text messages are transmitted every month) -- when I found myself

in Helsinki a few months after my Tokyo experience. I was sitting at an

outdoor cafe, drinking a cup of coffee, when three Finnish teenagers

encountered two older adults -- maybe the parents of one of them -- right

next to where I was sitting. I had no idea what they were saying -- they

were speaking Finnish -- but I noted that one of the teenagers glanced at

his mobile phone (all Finns carry their telephones in their hands and

glance at them from time to time) and smiled. Then he showed the telephone

display screen to the other two teenagers, who also smiled -- but he did

not show it to the other, older, adults. And all five of them continued

conversing as if this was normal.

I started asking around, and both my Japanese and Finnish friends told me

that many young adults "flocked" -- showed up at the same mall or

fast-food joint at the same time from eight different directions --

because they had coordinated and negotiated through flurries of text

messages.

Again, this was curious, but not world-shaking. I started doing some more

serious research when I read reports about the "People Power II"

demonstrations in Manila. The Estrada government was accused of

corruption, and everyone in the Philippines was glued to their TV set for

a time, like Americans during the Watergate hearings, as the Philippine

Congress investigated Estrada. When Senators linked to Estrada abruptly

shut down the hearings, tens of thousands of Philippine citizens started

gathering in EDSA -- the same square where the anti-Marcos demonstrations

had taken place. But they showed up within minutes -- almost all of them

wearing black. In hours, millions showed up. It was all summoned and

coordinated by text messages. Telephone trees are old organizing tactics,

but cumbersome compared to texting. Once you get a text message, y ou can

forward it to everyone in your address book.

I realized that the flocking teenagers and the demonstrating Filipinos

were taking advantage of a recently-lowered threshold for collective

action. And when I looked into collective action, I realized that much

more could be in store. It was when I understood that the mobile

telephones so many people carry are becoming miniature computers and

Internet terminals that I began to realize that we are on the verge of the

third great wave of change, following and building upon -- and going far

beyond -- the PC and Internet waves.

inkwell.vue 166: Howard Rheingold, Smart Mobs

#3 of 82: virtual community or butter? (bumbaugh) Thu 21 Nov 2002 (01:28 PM)

So these "mobs" depend on particular technolgies in order to exist as

mobs. (And to be "smart" as well? Or is the smart part human, rather

than technological?) And they differ from what preceded them relying on

the Internet and PCs in being mobile (and relatively ubiquitous).

Anything else that's distinctive about the tech?

And why is this revolutionary, rather than just more of the same?

inkwell.vue 166: Howard Rheingold, Smart Mobs

#4 of 82: Howard Rheingold (hlr) Thu 21 Nov 2002 (01:47 PM)

Let's talk about the big picture for the moment: communication

technologies, social contracts, and collective action.

For a LONG time, humans hunted small game and gathered roots and berries

in small family groups. At some point, not all that long ago in our

evolutionary history, those family groups began to cooperate with others

who weren't directly related to them, organizing big-game hunts -- a form

of collective action that brought in more meat than any one family could

eat before it spoiled, thus creating the first public goods. Whenever a

means of communication, a social contract that enables people to trust one

another on a new scale, and collective action produce new public goods,

human society becomes more complex: agriculture, alphabets, printing

presses, etc. The printing press broke out the secret code of the

alphabet, which had been invented by the accountants for the first great

empires and had been reserved for the ruling elite for millennia. Within a

couple centuries of the emergence of literate populations, the collective

enterprises of self-governance and science emerged.

The Internet enables people to connect with strangers in other parts of

the world, getting together around shared affinities -- the whole virtual

community story. Ebay adds a reputation system, and a new market emerges.

Peer to peer methodologies enabled 70 million people to share their hard

disk space via Napster, and 2 million people to amass 20 trillion floating

point operations per second of CPU power to search for messages from outer

space.

What will happen when billions of people carry devices that are thousands

of times more powerful than today's PCs, linked at speeds thousands of

times faster than today's broadband connections, perhaps with distributed

reputation systems that enable us to find people with whom we have some

common cause -- on the fly, in the real world? That's the essential

question of smart mobs. The flocking teenagers, the Philippine

demonstrators, the Napster and SETI@home and eBay crowds -- they are only

the first outbreaks. After all, the PC I used when I first joined the Well

in 1985 had 640K RAM and communicated at 1200 baud. Now, fifteen years

later, I can access the Well from a handheld device (I use a Treo 300)

that is a thousand times more powerful, and a fifth the price. And the

speed is probably a thousand times faster.

This is not to say that smart mobs are wise mobs. Not all groups who use

new technologies to organize collective action have socially beneficial

ends in mind. Criminals, totalitarian governments, spammers, will all be

able to take advantage of new capabilities -- just as the first to take

advantage of tribes, nation-states, markets, networks included the

malevolent as well as the cooperative.

inkwell.vue 166: Howard Rheingold, Smart Mobs

#5 of 82: virtual community or butter? (bumbaugh) Thu 21 Nov 2002 (02:33 PM)

One aspect of the historical arc you're describing, Howard, is the

diminishing importance of geography or physical proximity in organizing

human affairs (or collective action, at any rate). Once upon a time,

our mates were limited to our mates (and offspring and forebears).

Spoken language made coordination and a host of personal relationships

feasible with others near enough to speak with. As communications

technologies developed, larger groups could work together across

distances.

Two important constraints were (1) a time lag that limited the pace of

activity and (2) central control over the technology (early on a

matter of limiting literacy, later owning the press or antenna) that

could try to limit who communicated and what.

PCs and the Net have made a serious dent in the second (setting aside

digital divide issues for the moment, but knowing we'll get back to

them): everyone's a publisher now. (I remember you made the point

forcefully in *The Virtual Community* that it was important to preserve

the ability to communicate "upstream" on the Net for that value to

flourish.)

PCs and the Net have surely altered the first radically, as well,

checked to a degree by the need to be at a jack in the wall to be

online.

But the new technologies you're describing are faster and nimbler. And

they travel with us. So they allow coordination with arbitrary people

wherever they are (without even having to meet them). They allow

coordinating right past other people who are physically near (as in

your Finnish teens example).

That change of pace and transformation of geography (replaced, I

guess, by various network topographies and other relationships?) does

seem profound. It would be surprising if our existing social norms and

habits regarding privacy, trust, and so on, proved to be easily applied

right out of the gate for dealing with this new arena.

If these technologies stand to empower some people (or The People),

that must threaten some other people. That was obviously true about

literacy and printing, and almost everyone reading Inkwell will be

familiar with the last decade of political wars over the Internet.

Are we on the brink of the greatest power struggle since the discovery

of fire?

inkwell.vue 166: Howard Rheingold, Smart Mobs

#6 of 82: Howard Rheingold (hlr) Thu 21 Nov 2002 (02:35 PM)

One other element regarding my contention that we are at the beginning of

a revolutionary wave of change: Mobile telephones, which are quickly

morphing into portable Internet terminals with significant and growing

onboard computation power, are used by people who have not had access to

PCs and the Net, and are used in parts of our lives that computation on

online communication have not reached.

One in eight people in Botswana have mobile telephones.

Six weeks ago, in Sao Paolo, I saw barefoot people in the slums talking on

their mobile telephones.

Somali traders of the coast of Dubai make deals via telephoneIn rural

Bangladesh, the mobile telephone has been introduced via payshops run by

local women -- and the shops have become new social centers.

The PC (except for laptops) and the Internet have been confined to

desktops. Now we carry computation and online communication into the

streets, automobiles, trains -- places where computing and instant global

communications were not available before.

inkwell.vue 166: Howard Rheingold, Smart Mobs

#7 of 82: Howard Rheingold (hlr) Thu 21 Nov 2002 (02:45 PM)

(Bruce slipped while I was adding that last post)

Part of Smart Mobs examines the relationship between knowledge,

communication and power -- most famously pioneered by Foucault -- and the

power struggles that cut through the many technological and sociological

issues raised by smart mobs. Central power versus decentralized power is

an ongoing arms raised. The Internet is now the site of control struggles:

Cable companies are merging, resisting wireless rebroadcast of bandwidth,

petitioning for the right to discriminate against content from competing